Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov - biography

- the second Tsar of Moscow from the house of the Romanovs, the son of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich and his second wife Evdokia Lukyanovna (Streshneva). Alexei Mikhailovich was born in 1629 and from the age of three he was brought up under the guidance of the boyar Boris Ivanovich Morozov, an intelligent and educated person for that time, slightly inclined towards "new" (Western) customs, but cunning and self-serving. Being with Tsarevich Alexei without a break for 13 years, Morozov acquired a very strong influence on his pet, who was distinguished by complacency and affection.

On July 13, 1645, 16-year-old Alexei Mikhailovich inherited the throne of his father, and, as can be seen from the testimony Kotoshikhina, indirectly confirmed by some other indications (for example, Olearia), followed by the convocation of the Zemsky Sobor, which sanctioned the accession of the new sovereign - a sign that, according to the views of the people of the 17th century, the suffrage of the land, expressed in the act of electing Mikhail Romanov to the kingdom in 1613, did not stop with the death of the first tsar from the new Romanov dynasty. According to Kotoshikhin, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, like his father, was elected to the kingdom by people of all ranks of the Muscovite state, however, without limiting (vowel or secret) his royal power due to a purely subjective reason - the personal character of the young tsar, who was reputed to be "much quiet" and who retained for himself not only in the mouths of his contemporaries, but also in history the nickname "the quietest." Consequently, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich ruled more autocratically than his father. Inherited from the Time of Troubles, the habit and need to seek assistance from the zemstvo weakened under him. Zemstvo sobors, especially full ones, are still convened, but much less frequently, especially in the later years of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov, and the command principle in state life gradually takes precedence over the zemstvo one under him. The king finally becomes the embodiment of the nation, the center from which everything emanates and to which everything returns. Such a development of the autocratic principle corresponds to the external situation of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich: an unheard-of development of court splendor and etiquette, which, however, did not eliminate the simple-minded, patriarchal treatment of the tsar with his entourage.

Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. Late 1670s

Not immediately, however, Alexei Mikhailovich could put his power to an unattainable height: the first years of his reign are reminiscent of the events of the youth of Ivan the Terrible or the difficulties that Tsar Mikhail had to fight at first. After the death of his mother (August 18 of the same 1645), Alexei Mikhailovich completely submitted to the influence of Morozov, who no longer had rivals. The latter, in order to strengthen his position, managed to resolve the issue of the tsar's marriage in a sense desirable for himself by arranging his marriage with the daughter of his faithful assistant, Maria Ilyinichnaya Miloslavskaya. This marriage was concluded on January 16, 1648, after the bride, originally chosen by Alexei Mikhailovich (Vsevolozhskaya) himself, was eliminated under the pretext of epilepsy. Morozov himself married the sister of the new queen. The royal father-in-law Miloslavsky and Morozov, taking advantage of their position, began to nominate their relatives and friends, who did not miss an opportunity to profit. While the young Alexei Mikhailovich, relying in everything on his beloved and revered “second father”, did not delve into matters personally, discontent accumulated among the people: on the one hand, the lack of justice, extortion, the severity of taxes, the salt duty introduced in 1646 (cancelled at the beginning of 1648), in conjunction with crop failure and bestial mortality, and on the other hand, the ruler's goodwill towards foreigners (proximity to Morozov and the influential position of the breeder Vinius) and foreign customs (permission to consume tobacco, made the subject of a state monopoly), - all this in May 1648 led to a bloody catastrophe - the "salt riot". The direct appeal of the crowd in the street to Alexei Mikhailovich himself, to whom complaints did not reach in any other way due to the rude intervention of Morozov's minions, broke out into a mutiny that lasted several days, complicated by a strong fire, which, however, served to stop further unrest. Morozov managed to be saved from the fury of the crowd and sheltered in the St. Cyril's Belozersky Monastery, but his accomplices paid all the more: the duma clerk Nazar Chisty, who was killed by the rebels, and the hated heads of the zemstvo and Pushkar orders, Pleshcheev and Trakhaniotov, who had to be sacrificed, extraditing them for execution, moreover the first was even torn from the hands of the executioner and barbarously killed by the crowd itself. When the excitement subsided, Alexei Mikhailovich personally addressed the people on the appointed day and touched them with the sincerity of his promises so much that the main culprit of what happened, Morozov, for whom the tsar asked, could soon return to Moscow; but his dominion is over forever.

![]()

Salt Riot in Moscow 1648. Painting by E. Lissner, 1938

The Moscow rebellion responded in the same year with similar outbreaks in remote Solvychegodsk and Ustyug; in January 1649, new attempts of indignation, again suppressed against Morozov and Miloslavsky, were discovered in Moscow itself. Much more serious were the rebellions that broke out in 1650 in Novgorod and Pskov, where at the beginning of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, bread was bought to pay the Swedes a part of the agreed amount for defectors from the regions that had ceded to Sweden under the Peace of Stolbov 1617. The rise in the price of grain exported abroad gave rise to rumors about the betrayal of the boyars, who run everything without the knowledge of the tsar, who are friends with foreigners and, together with them, are plotting to starve out the Russian land. To pacify the riots, it was necessary to resort to exhortations, and to explanations, and to military force, especially with regard to Pskov, where the unrest stubbornly continued for several months.

However, in the midst of these unrest and turmoil, the government of Alexei Mikhailovich managed to complete legislative work of very great importance - the codification of the Cathedral Code of 1649. According to the long-standing desire of Russian trading people, in 1649 the English company was deprived of its privileges, the reason for which, in addition to various abuses, was the execution of King Charles I: from now on, English merchants were allowed to trade only in Arkhangelsk and with the payment of the usual fee. The reaction against the beginning rapprochement with foreigners and the assimilation of foreign customs was reflected in the renewal of the ban on the tobacco trade. Despite the efforts of the British government after the restoration of the Stuarts, the former benefits to the British were not renewed.

But the restriction of foreign trade within the state led in the subsequent years of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, when the wars with Poland and Sweden required an extreme strain of payment forces, unforeseen consequences: the treasury had to be pulled into the treasury as large as possible stocks of silver coins, and meanwhile a strong reduction in the import of silver was discovered. , previously supplied by English merchants in bullion and in specie, which was then re-coined. The government of Alexei Mikhailovich resorted from 1655 to the issuance of copper money, which was supposed to go on an equal footing and at the same price with silver, which, however, soon turned out to be impossible, since, paying salaries in copper, the treasury demanded payment of fees and arrears without fail in silver, and excessive issues of copper coins and without that, making the exchange a fiction, led to a rapid depreciation. Finally, the production of counterfeit money, which also developed on an enormous scale, completely undermined the confidence in the new means of payment, and an extreme depreciation of copper followed, and, consequently, an exorbitant rise in the price of all purchased items. In 1662, the financial crisis broke out in a new rebellion in Moscow (“Copper Riot”), from where the crowd rushed to the village of Kolomenskoye, Alexei Mikhailovich’s favorite summer residence, demanding the extradition of the boyars, who were considered guilty of abuses and general disaster. This time the unrest was pacified by armed force, and the rebels suffered severe retribution. But copper money, which was still in circulation for a whole year and fell in price 15 times against its normal value, was then destroyed.

Copper Riot. Painting by E. Lissner, 1938

The state experienced an even more severe shock in 1670-71, when it had to endure a life-and-death struggle with the Cossack freemen, who found a leader in the person of Stenka Razin and carried away the masses of the black people and the Volga non-Russian population. The government of Alexei Mikhailovich, however, turned out to be strong enough to overcome the aspirations hostile to him and to withstand the dangerous struggle of a social nature.

Stepan Razin. Painting by S. Kirillov, 1985-1988

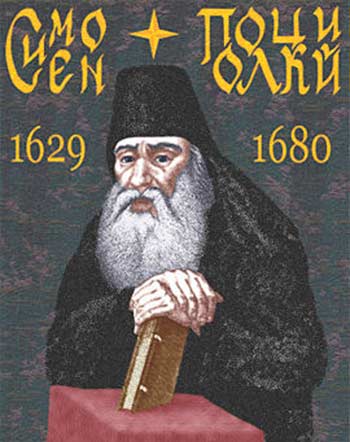

Finally, the era of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov also includes a serious crisis in the church life of the Russian people, the beginning of a centuries-old bifurcation caused by Nikon's "innovations", but rooted in the very depths of the people's worldview. The church schism openly expressed the adherence of the Russian people to their own national principles. The mass of the Russian population began a desperate struggle to preserve their shrine, against the influx of new, Ukrainian and Greek influences, which, as the end of the 17th century approached, was felt more and more closely. Severe repressive measures by Nikon, persecution and exile, which resulted in an extreme aggravation of religious passions, exalted martyrdom mercilessly persecuted for adherence to Russian customs of "schismatics", to which they responded with voluntary self-immolations or self-burials - such is, in general terms, the picture of the situation created by the ambition of the patriarch, who started his reform most of all for the purpose of personal self-exaltation. Nikon hoped that the glory of the purifier of the Russian church from imaginary heresy would help him advance to the role heads of the entire Orthodox world , to rise above his other patriarchs and Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich himself. Nikon's unheard-of power-hungry encroachments led to a sharp clash between him and the complacent tsar. The patriarch, who in one of the periods of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich had unlimited influence on the tsar and the entire course of state affairs, the second "great sovereign", the closest (after Morozov's removal) friend and adviser to the monarch, quarreled with him and left his throne. The unfortunate conflict ended with the conciliar court of 1666-1667, which deprived the patriarch of his holy dignity and condemned him to imprisonment in a monastery. But the same council of 1666-1667 confirmed Nikon's main cause and, having imposed an irrevocable anathema on his opponents, finally destroyed the possibility of reconciliation and declared decisive war on the schism. It was accepted: for 8 years (1668 - 1676), the royal governors had to besiege the Solovetsky Monastery, one of the most revered popular shrines, which has now become a stronghold of national antiquity, take it by storm and hang the captured rebels.

Alexei Mikhailovich and Nikon at the tomb of Saint Metropolitan Philip. Painting by A. Litovchenko

Simultaneously with all these difficult internal events of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, from 1654 until the very end of his reign, external wars did not stop, the impetus for which was given by the events in Little Russia, where Bogdan Khmelnitsky raised the banner of religious-national struggle. Bound at the beginning by the unfavorable Polyanovsky peace, concluded under his father, maintaining friendly relations with Poland in the early years (a plan of common actions against the Crimea), Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov could not abandon the centuries-old traditions of Moscow, from its national tasks. After some hesitation, he had to act as a resolute intercessor for the Orthodox Russian southwest and take Hetman Bogdan under his hand with all of Ukraine, which meant war with Poland. It was difficult to decide on this step, but not to take advantage of the favorable opportunity to fulfill long-standing cherished aspirations, to push Little Russia away from itself with the risk that it would throw itself into the arms of Turkey, would mean renouncing its mission and committing political recklessness that is difficult to correct. The issue was resolved at the Zemsky Sobor of 1653, followed by the swearing of the oath to Tsar Alexei by the Ukrainians at the Rada in Pereyaslavl (January 8, 1654), and Little Rus' officially passed under the power of the Moscow Tsar on conditions that ensured its autonomy. The immediately opened war, in which Alexei Mikhailovich took a personal part, was marked by the brilliant, hitherto unprecedented successes of Moscow weapons, the conquest of Smolensk, captured in the Time of Troubles and finally taken away in peace in 1654, all of Belarus, even native Lithuania with its capital Vilna ( -). The Muscovite sovereign adopted in his title the title of "All Great, Small and White Rus' autocrat", as well as the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

Pereyaslav Rada 1654. Painting by M. Khmelko, 1951

The age-old dispute seemed close to being resolved; Poland, which had brought upon itself the still victorious Swedish invasion, was on the verge of destruction, but it was precisely the joint actions against it of two enemies who were by no means allies, but rather interfered with each other and claimed the same booty (Lithuania), served to save the Rech Commonwealth. The intervention of Austria, friendly and of the same faith to the Poles, interested in supporting Poland against an excessively strengthened Sweden, managed, with the help of the Allegretti embassy, to persuade Aleksei Mikhailovich to a truce with Poland in 1656, with the retention of the conquered and with a deceptive hope for the future election of him to the Polish throne. More importantly, the Austrians and Poles managed to induce the king to go to war with Sweden, as a much more dangerous enemy. This new war with the Swedes, in which Alexei Mikhailovich also personally participated (since 1656), was very untimely until the dispute with Poland was finally resolved. But it was difficult to avoid it for the reasons stated: believing that in the near future he would become the king of Poland, Alexei Mikhailovich even turned out to be personally interested in preserving it. Having started the war, Alexei Mikhailovich decided to try to carry out another long-standing and no less important historical task of Russia - to break through to the Baltic Sea, but the attempt was unsuccessful, it turned out to be premature. After initial successes (the capture of Dinaburg, Kokenhausen, Dorpat), they had to suffer a complete setback during the siege of Riga, as well as Noteburg (Nutlet) and Kexholm (Korela). The peace of Cardis in 1661 was a confirmation of Stolbovsky, that is, everything taken during the campaign of Alexei Mikhailovich was given back to the Swedes.

Such a concession was forced by the troubles that began in Little Russia after the death of Khmelnitsky (1657) and the renewed Polish war. The accession of Little Russia was far from being lasting: displeasure and misunderstanding were not slow to arise between the "Muscovites" and "Khokhls", who in many ways were very different from each other and were still poorly acquainted with each other. The desire of the region, which voluntarily succumbed to Russia and Alexei Mikhailovich, to keep intact its administrative independence from it, met with the Moscow tendency to the possible unification of government and all external forms of life. The independence granted to the hetman not only in the internal affairs of Ukraine, but also in international relations, was hardly consistent with the autocratic power of the Russian tsar. The Cossack military aristocracy felt freer under the Polish order than under the Moscow one, and could not get along with the tsarist governors, whom, however, the common people, who were more attracted to the same faith tsarist Moscow than to gentry Poland, had more than once reason to complain. Already Bogdan had troubles with the government of Alexei Mikhailovich, could not get used to new relations, was very dissatisfied with the end of the Polish war and the start of the Swedish war. After his death, a struggle for hetmanship opened up, a long chain of intrigues and civil strife, vacillation from side to side, denunciations and accusations, in which it was difficult not to get confused by the government. Vygovsky, who seized the hetmanate from the too young and incapable Yuri Khmelnitsky, a gentry by birth and sympathies, secretly transferred to Poland on the most apparently tempting terms of the Gadyach Treaty (1658) and, with the help of the Crimean Tatars, inflicted a severe defeat on Prince Trubetskoy near Konotop (1659) . The case of Vyhovsky nevertheless failed due to the lack of sympathy for him among the ordinary Cossack masses, but the Little Russian troubles did not end there.

Hetman Ivan Vyhovsky

At the same time, the war with Poland resumed, having managed to get rid of the Swedes and now violated recent promises to elect Alexei Mikhailovich as their king in the hope of Ukrainian unrest. The election of Tsar Alexei to the Polish throne, which had previously been promised only in the form of a political maneuver, was no longer a question. After the first successes (the victory of Khovansky over Gonsevsky in the autumn of 1659), the war with Poland went far less successfully for Russia than in the first stage (the defeat of Khovansky by Charnetsky at Polonka, the betrayal of Yuri Khmelnitsky, the disaster at Chudnov, Sheremetev in the Crimean captivity - 1660 city; loss of Vilna, Grodno, Mogilev - 1661). The right bank of the Dnieper was almost lost: after the refusal of the hetmanship of Khmelnytsky, who took the monastic vows, Teterya, who swore allegiance to the Polish king, also turned out to be his successor. But on the left side, which remained behind Moscow, after some troubles, another hetman appeared - Bryukhovetsky: this was the beginning of the political division of Ukraine. In 1663 - 64 years. The Poles fought with success on the left side, but they could not take Glukhov and retreated with heavy losses behind the Desna. After long negotiations, both states, extremely tired of the war, finally concluded in 1667 for 13 and a half years the famous Andrusovo truce, which cut Little Russia in two. Alexei Mikhailovich received Smolensk and Seversk land lost by his father and acquired the left-bank Ukraine. However, only Kyiv with its immediate environs remained on the right bank behind Russia (at first it was ceded by the Poles only temporarily, for two years, but then not given back by Russia).

Such an outcome of the war could be considered successful by the government of Alexei Mikhailovich, but it was far from meeting the initial expectations (for example, regarding Lithuania). To a certain extent, satisfying the national pride of Moscow, the Treaty of Andrusov greatly disappointed and irritated the Little Russian patriots, whose fatherland was divided and more than half returned under the hated dominion, from which they tried to break out for so long and with such efforts (Kievshchina, Volyn, Podolia , Galicia, not to mention White Rus'). However, the Ukrainians themselves contributed to this with their constant betrayals of the Russians and throwing in the war from side to side. The Little Russian unrest did not stop, but even became more complicated after the Andrusovo truce. The hetman of the right-bank Ukraine, Doroshenko, who did not want to obey Poland, who was ready to serve the government of Alexei Mikhailovich, but only under the condition of complete autonomy and the indispensable connection of all Ukraine, decided, due to the impracticability of the latter condition, to pass under the hand of Turkey in order to achieve the unification of Little Russia under her rule. The danger posed by Turkey to both Moscow and Poland prompted these former enemies, already at the end of 1667, to conclude an agreement on joint actions against the Turks. This treaty was then renewed with King Mikhail Vyshnevetsky in 1672, and in the same year the Sultan invaded the Ukraine. Mehmed IV, which was joined by the Crimean Khan and Doroshenko, the capture of Kamenets and the conclusion by the king of a humiliating peace with the Turks, who, however, did not stop the war. The troops of Alexei Mikhailovich and the left-bank Cossacks in 1673 - 1674 successfully operated on the right side of the Dnieper, and a significant part of the latter again submitted to Moscow. In 1674, right-bank Ukraine experienced the horrors of the Turkish-Tatar devastation for the second time, but the Sultan's hordes again withdrew without uniting Little Russia.

On January 29, 1676, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich died. His first wife died already on March 2, 1669, after which Alexei, who became extremely attached to his new favorite, the boyar Artamon Matveev, married a second time (January 22, 1671) to his distant relative Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina. Soon she gave birth to a son from Alexei Mikhailovich - the future Peter the Great. Already earlier, in the first years of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, European influences penetrated Moscow under the auspices of Morozov. Then the annexation of Little Russia with its schools gave a new strong impetus towards the West. It resulted in the appearance and activity of Kiev scientists in Moscow, the founding by Rtishchev of the Andreevsky Monastery with a learned brotherhood, the activities of Simeon of Polotsk, a tireless writer in verse and prose, a preacher and mentor of the elder royal sons, in general, the transfer of Latin-Polish and Greek-Slavic scholasticism to new soil . Further, the favorite of Alexei Mikhailovich Ordin-Nashchokin, the former head of the embassy order, is an "imitator of foreign customs", the founder of post offices for foreign correspondence and the founder of handwritten chimes (the first Russian newspapers); and the clerk of the same order, Kotoshikhin, who fled abroad, and the author of a well-known essay on contemporary Russia, also appears to be an undoubted and ardent Westernizer. In the era of Matveev's power, cultural borrowings become even more tangible: from 1672, foreigners appeared at the court of Alexei Mikhailovich, and then their own "comedians", the first theatrical "performances" begin to play out. The tsar and the boyars get European carriages, new furniture, in other cases foreign books, friendship with foreigners, knowledge of languages. Tobacco smoking is no longer prosecuted as before. The seclusion of women is coming to an end: the tsarina already rides in an open carriage, is present at theatrical performances, the daughters of Alexei Mikhailovich even learn from Simeon of Polotsk.

The proximity of the era of decisive transformations is clearly felt in all these facts, as well as in the beginning military reorganization in the appearance of regiments of the "foreign system", in the decline of obsolete localism, in an attempt to build a fleet (the shipyard in the village of Dednovo, the ship "Eagle", burned by Razin on the lower Volga; the idea of farming Courland harbors for Russian ships), in the beginning of the construction of factories, in an effort to break through to the sea in the west. The diplomacy of Alexei Mikhailovich gradually spreads to all of Europe, including Spain, while in Siberia Russian dominion has already reached the Great Ocean, and the establishment on the Amur led to the first acquaintance and then a clash with China.

Yenisei Territory, Baikal and Transbaikalia in the era of the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich

The reign of Alexei Mikhailovich represents an era of transition from old Rus' to new Russia, a difficult era, when backwardness from Europe made itself felt at every step and failures in the war, and sharp turmoil within the state. The government of Alexei Mikhailovich was looking for ways to satisfy the increasingly complex tasks of domestic and foreign policy, was already aware of its backwardness in all spheres of life and the need to embark on a new road, but did not yet dare to declare war on the old isolation and tried to get by with the help of palliatives. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was a typical man of his era, who combined a strong attachment to the old tradition with a love for useful and pleasant innovations: standing still firmly on the old soil, being a model of ancient Russian piety and patriarchy, he already puts one foot on the other side. A man of a more lively and mobile temperament than his father (Alexei Mikhailovich’s personal participation in campaigns), inquisitive, affable, hospitable and cheerful, at the same time a zealous pilgrimage and fasting, an exemplary family man and a model of complacency (albeit with sometimes strong temper) - Alexei Mikhailovich was not a man of strong character, he was deprived of the qualities of a transformer, he was capable of innovations that did not require drastic measures, but he was not born to fight and break, like his son Peter I. His ability to become strongly attached to people (Morozov, Nikon, Matveev ) and his kindness could easily lead to evil, opening the way for all kinds of influences during his reign, creating omnipotent temporary workers and preparing future party struggles, intrigues and disasters like the events of 1648.

The favorite summer residence of Alexei Mikhailovich was the village of Kolomenskoye, where he built himself a palace; favorite pastime is falconry. Dying, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich left a large family: his second wife Natalia, three sisters, two sons (Fyodor and Ivan) and six daughters (see Tsarevna Sofya) from his first wife, son Peter (born May 30, 1672) and two daughters from the second wife. Two camps of his relatives through two different wives - the Miloslavskys and the Naryshkins - were not slow after his death to start a struggle among themselves, rich in historical consequences.

Literature on the biography of Alexei Mikhailovich

S. M. Solovyov, “History of Russia from ancient times”, vol. X – XII;

N. I. Kostomarov, “Russian history in the biographies of its main figures”, vol. II, part 1: “Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich”;

V. O. Klyuchevsky, “Course of Russian History”, part III;