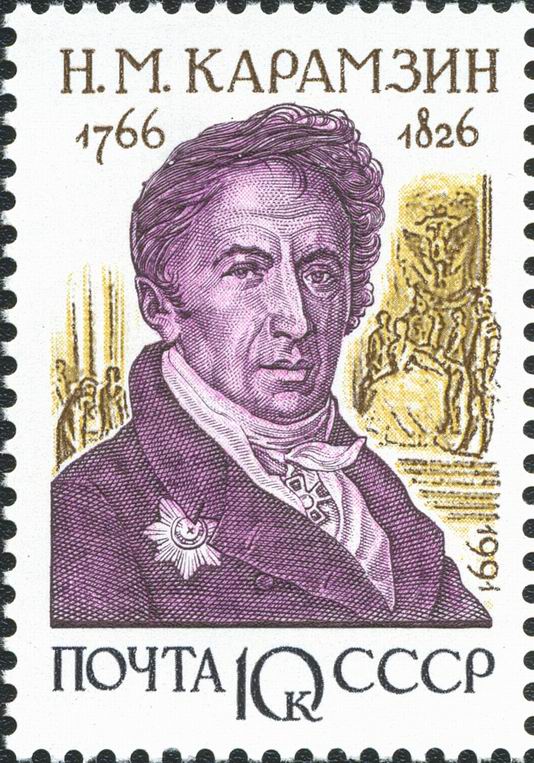

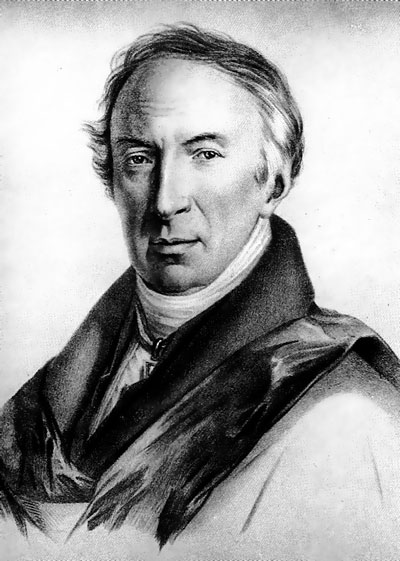

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin

(December 1, 1766, family estate Znamenskoye, Simbirsk district, Kazan province (according to other sources - the village of Mikhailovka (Preobrazhenskoye), Buzuluk district, Kazan province) - May 22, 1826, St. Petersburg)

Biography

Childhood, teaching, environment

Born in the family of a middle-class landowner of the Simbirsk province M. E. Karamzin. Lost his mother early. From early childhood, he began to read books from his mother's library, French novels, Ch. Rollin's "Roman History", the works of F. Emin, etc. Having received his initial education at home, he studied at a noble boarding school in Simbirsk, then at one of the best private boarding schools Professor of Moscow University I. M. Shaden, where in 1779-1880 he studied languages; He also listened to lectures at Moscow University.

In 1781 he began serving in the Preobrazhensky Regiment in St. Petersburg, where he became friends with A.I. and I.I. Dmitriev. This is a time not only of intense intellectual pursuits, but also of the pleasures of secular life. After the death of his father, Karamzin retired in 1784 as a lieutenant and never served again, which was perceived in the then society as a challenge. After a short stay in Simbirsk, where he joined the Masonic Lodge, Karamzin moved to Moscow and was introduced into the circle of N. I. Novikov, settled in a house that belonged to the Novikov Friendly Scientific Society (1785).

1785-1789 - years of communication with Novikov, at the same time he also became close to the Pleshcheev family, and for many years he was connected with N. I. Pleshcheeva by a tender platonic friendship. Karamzin publishes his first translations and original writings, in which interest in European and Russian history is clearly visible. Karamzin is the author and one of the publishers of the first children's magazine "Children's Reading for the Heart and Mind" (1787-1789), founded by Novikov. Karamzin will retain a feeling of gratitude and deep respect for Novikov for life, speaking in his defense in subsequent years.

European travel, literary and publishing activities

Karamzin was not disposed towards the mystical side of Freemasonry, remaining a supporter of its active and educational direction. Perhaps the coolness towards Freemasonry was one of the reasons for Karamzin's departure to Europe, where he spent more than a year (1789-90), visiting Germany, Switzerland, France and England, where he met and talked (except for influential Masons) with European "rulers of minds ”: I. Kant, I. G. Herder, C. Bonnet, I. K. Lavater, J. F. Marmontel and others, visited museums, theaters, secular salons. In Paris, he listened to O. G. Mirabeau, M. Robespierre and others in the National Assembly, saw many prominent political figures and was familiar with many. Apparently, revolutionary Paris showed Karamzin how much a person can be influenced by the word: printed, when Parisians read pamphlets and leaflets, newspapers with keen interest; oral, when revolutionary orators spoke and controversy arose (experience that could not be acquired in Russia).

Karamzin did not have a very enthusiastic opinion about English parliamentarism (perhaps following in the footsteps of Rousseau), but he highly valued the level of civilization at which English society as a whole was located.

Moscow Journal and Vestnik Evropy

Returning to Moscow, Karamzin began publishing the Moscow Journal, in which he published the story Poor Liza (1792), which had an extraordinary success with readers, then Letters from a Russian Traveler (1791-92), which put Karamzin among the first Russian writers. In these works, as well as in literary critical articles, the aesthetic program of sentimentalism was expressed with its interest in a person, regardless of class, his feelings and experiences. In the 1890s, his interest in the history of Russia increased; he gets acquainted with historical works, the main published sources: chronicle monuments, notes of foreigners, etc.

Karamzin's response to the coup on March 11, 1801 and the accession to the throne of Alexander I was perceived as a collection of examples to the young monarch "Historical eulogy to Catherine II" (1802), where Karamzin expressed his views on the essence of the monarchy in Russia and the duties of the monarch and his subjects.

Interest in the history of the world and domestic, ancient and new, the events of today prevails in the publications of the first in Russia socio-political and literary-artistic journal Vestnik Evropy, published by Karamzin in 1802-03. He also published here several works on Russian medieval history (“Martha Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod”, “The News of Martha Posadnitsa, taken from the Life of St. Zosima”, “Journey Around Moscow”, “Historical Memoirs and Notes on the Way to the Trinity” and others), testifying to the intention of a large-scale historical work, and the readers of the journal were offered some of its plots, which made it possible to study the reader's perception, improve the techniques and methods of research, which will then be used in the History of the Russian State.

Historical writings

In 1801 Karamzin married E. I. Protasova, who died a year later. By the second marriage, Karamzin was married to the half-sister of P. A. Vyazemsky, E. A. Kolyvanova (1804), with whom he lived happily until the end of his days, finding in her not only a devoted wife and caring mother, but also a friend and assistant in historical studies .

In October 1803, Karamzin obtained from Alexander I the appointment of a historiographer with a pension of 2,000 rubles. for writing Russian history. Libraries and archives were opened for him. Until the last day of his life, Karamzin was busy writing the "History of the Russian State", which had a significant impact on Russian historical science and literature, allowing us to see in it one of the most notable cultural-forming phenomena not only of the entire 19th century, but also of the 20th. Starting from ancient times and the first mention of the Slavs, Karamzin managed to bring the "History" to the Time of Troubles. This amounted to 12 volumes of a text of high literary merit, accompanied by more than 6 thousand historical notes, in which historical sources, works by European and Russian authors were published and analyzed.

During the life of Karamzin, "History" managed to come out in two editions. Three thousand copies of the first 8 volumes of the first edition were sold out in less than a month - "the only example in our land," according to Pushkin. After 1818, Karamzin published volumes 9-11, the last, volume 12, came out after the death of the historiographer. "History" was published several times in the 19th century, and in the late 1980s-1990s more than ten modern editions were published.

Karamzin's view of the arrangement of Russia

In 1811, at the request of Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna, Karamzin wrote a note "On ancient and new Russia in its political and civil relations", in which he outlined his ideas about the ideal structure of the Russian state and sharply criticized the policy of Alexander I and his immediate predecessors: Paul I, Catherine II and Peter I. In the 19th century. this note was never published in its entirety and was scattered in handwritten lists. In Soviet times, it was perceived as a reaction of the extremely conservative nobility to the reforms of M. M. Speransky, however, during the first full publication of the note in 1988, Yu. M. Lotman revealed its deeper content. Karamzin in this document criticized unprepared bureaucratic reforms carried out from above. The note remains in Karamzin's work the most complete expression of his political views.

Karamzin had a hard time with the death of Alexander I and especially the Decembrist uprising, which he witnessed. This took away the last of his vitality, and the slowly fading historiographer died in May 1826.

Karamzin is perhaps the only example of a person in the history of Russian culture, about whom contemporaries and descendants did not have any ambiguous memories. Already during his lifetime, the historiographer was perceived as the highest moral authority; this attitude towards him remains unchanged to this day.

Bibliography

Works by Karamzin

* "Bornholm Island" (1793)

* "Julia" (1796)

* "Martha the Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod", a story (1802)

* "Autumn"

Memory

* Named after the writer:

* Passage of Karamzin in Moscow.

* Established: Monument to N. M. Karamzin in Simbirsk/Ulyanovsk

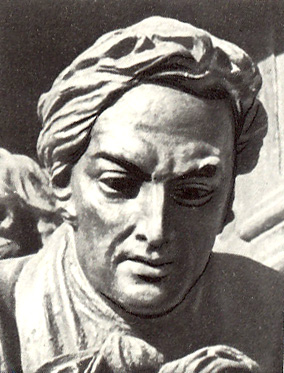

* In Veliky Novgorod, on the Monument "1000th Anniversary of Russia" among 129 figures of the most prominent personalities in Russian history (for 1862) there is a figure of N. M. Karamzin

Biography

Karamzin Nikolai Mikhailovich, a famous writer and historian, was born on December 12, 1766 in Simbirsk. He grew up in the estate of his father, a middle-class Simbirsk nobleman, a descendant of the Tatar murza Kara-Murza. He studied with a rural deacon, later, at the age of 13, Karamzin was assigned to the Moscow boarding school of Professor Shaden. In parallel, he attended classes at the university, where he studied Russian, German, French.

After graduating from the Shaden boarding school, Karamzin in 1781 entered the service in the St. Petersburg Guards Regiment, but soon retired due to lack of funds. The first literary experiments date back to the time of military service (translation of Gessner's idyll "Wooden Leg" (1783), etc.). In 1784 he joined a Masonic lodge and moved to Moscow, where he became close to Novikov's circle and contributed to its publications. In 1789-1790. traveled in Western Europe; then he began to publish the Moscow Journal (until 1792), where Letters from a Russian Traveler and Poor Lisa were published, which brought him fame. The collections published by Karamzin marked the beginning of the era of sentimentalism in Russian literature. The early prose of Karamzin influenced the work of V. A. Zhukovsky, K. N. Batyushkov, and the young A. S. Pushkin. The defeat of Freemasonry by Catherine, as well as the brutal police regime of the Pavlovian reign, forced Karamzin to curtail his literary activity, limiting himself to reprinting old editions. He met the accession of Alexander I with a laudatory ode.

In 1803, Karamzin was appointed official historiographer. Alexander I instructs Karamzin to write the history of Russia. From that time until the end of his days, Nikolai Mikhailovich has been working on the main work of his life. Since 1804, he took up compiling the "History of the Russian State" (1816-1824). The twelfth volume was published after his death. Careful selection of sources (many were discovered by Karamzin himself) and critical notes give special value to this work; rhetorical language and constant moralizing were already condemned by contemporaries, although they were liked by a large public. Karamzin at that time was inclined to extreme conservatism.

A significant place in the legacy of Karamzin is occupied by works devoted to the history and current state of Moscow. Many of them were the result of walks around Moscow and trips to its environs. Among them are the articles “Historical Memoirs and Remarks on the Way to the Trinity”, “On the Moscow Earthquake of 1802”, “Notes of an Old Moscow Resident”, “Journey Around Moscow”, “Russian Antiquity”, “On Light Clothing of Fashionable Beauties of the ninth to ten century." Died in St. Petersburg on June 3, 1826.

Biography

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was born near Simbirsk in the family of retired captain Mikhail Yegorovich Karamzin, a middle-class nobleman, a descendant of the Crimean Tatar Murza Kara-Murza. He was educated at home, from the age of fourteen he studied in Moscow at the boarding house of Professor Schaden of Moscow University, while attending lectures at the University. In 1783, at the insistence of his father, he entered the service in the St. Petersburg Guards Regiment, but soon retired. The first literary experiments date back to this time.

In Moscow, Karamzin became close with writers and writers: N. I. Novikov, A. M. Kutuzov, A. A. Petrov, participated in the publication of the first Russian magazine for children - “Children's Reading for the Heart and Mind”, translated German and English sentimental authors: plays by W. Shakespeare and G.E. Lessing and others. For four years (1785-1789) he was a member of the Masonic lodge "Friendly Learned Society". In 1789-1790. Karamzin traveled to Western Europe, where he met many prominent representatives of the Enlightenment (Kant, Herder, Wieland, Lavater, etc.), was in Paris during the great French Revolution. Upon returning to his homeland, Karamzin published Letters from a Russian Traveler (1791-1792), which immediately made him a famous writer. Until the end of the 17th century, Karamzin worked as a professional writer and journalist, published the Moscow Journal 1791-1792 (the first Russian literary magazine), published a number of collections and almanacs: Aglaya, Aonides, Pantheon of Foreign Literature, My knickknacks." During this period, he wrote many poems and stories, the most famous of which: "Poor Liza." Karamzin's activities made sentimentalism the leading trend in Russian literature, and the writer himself became the called leader of this trend.

Gradually, Karamzin's interests shifted from the field of literature to the field of history. In 1803, he published the story "Marfa the Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod" and as a result received the title of imperial historiographer. The following year, the writer practically stops his literary activity, concentrating on the creation of the fundamental work "History of the Russian State". Before the publication of the first 8 volumes, Karamzin lived in Moscow, from where he traveled only to Tver to the Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna and to Nizhny, while Moscow was occupied by the French. He usually spent his summers at Ostafyev, the estate of Prince Andrei Ivanovich Vyazemsky, whose daughter, Ekaterina Andreevna, Karamzin married in 1804 (Karamzin's first wife, Elizaveta Ivanovna Protasova, died in 1802). The first eight volumes of The History of the Russian State went on sale in February 1818, the three thousandth edition sold out within a month. According to contemporaries, Karamzin revealed to them the history of his native country, just as Columbus discovered America to the world. A.S. Pushkin called his work not only the creation of a great writer, but also "the feat of an honest man." Karamzin worked on his main work until the end of his life: the 9th volume of "History ..." was published in 1821, 10 and 11 - in 1824, and the last 12th - after the death of the writer (in 1829). Karamzin spent the last 10 years of his life in St. Petersburg and became close to the royal family. Karamzin died in St. Petersburg, as a result of complications after suffering pneumonia. He was buried at the Tikhvin cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

Interesting facts from life

Karamzin owns the most concise description of public life in Russia. When, during his trip to Europe, Russian emigrants asked Karamzin what was happening in his homeland, the writer answered with one word: "They steal."

Some philologists believe that modern Russian literature dates back to Karamzin's Letters of a Russian Traveler.

Writer's Awards

Honorary member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences (1818), full member of the Imperial Russian Academy (1818). Cavalier of the orders of St. Anna, 1st degree and St. Vladimir, 3rd degree /

Bibliography

Fiction

* Letters from a Russian traveler (1791–1792)

* Poor Liza (1792)

* Natalia, boyar daughter (1792)

* Sierra Morena (1793)

* Bornholm Island (1793)

* Julia (1796)

* My Confession (1802)

* Knight of our time (1803)

Historical and historical-literary works

* Marfa the Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod (1802)

* Note on ancient and new Russia in its political and civil relations (1811)

* History of the Russian state (vols. 1-8 - in 1816-1817, vol. 9 - in 1821, vol. 10-11 - in 1824, vol. 12 - in 1829)

Screen adaptations of works, theatrical performances

* Poor Liza (USSR, 1978), puppet cartoon, dir. Garanin's idea

* Poor Lisa (USA, 2000) dir. Slava Zuckerman

* History of the Russian State (TV) (Ukraine, 2007) dir. Valery Babich

Biography

Russian historian, writer, publicist, founder of Russian sentimentalism. Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was born on December 12 (December 1 according to the old style) 1766 in the village of Mikhailovka, Simbirsk province (Orenburg region), in the family of a Simbirsk landowner. He knew German, French, English, Italian. He grew up in his father's village. At the age of 14, Karamzin was brought to Moscow and given to a private boarding school of Moscow University professor I.M. Shaden, where he studied from 1775 to 1781. At the same time he attended lectures at the university.

In 1781 (some sources indicate 1783), at the insistence of his father, Karamzin was appointed to the Life Guards Preobrazhensky Regiment in St. Petersburg, where he was recorded as a minor, but at the beginning of 1784 he retired and left for Simbirsk, where he joined the Golden Crown Masonic lodge ". On the advice of I.P. Turgenev, who was one of the founders of the lodge, at the end of 1784 Karamzin moved to Moscow, where he joined the Masonic "Friendly Scientific Society", of which N.I. Novikov, who had a great influence on the formation of the views of Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin. At the same time, he collaborated with Novikov's magazine "Children's Reading". Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was a member of the Masonic Lodge until 1788 (1789). From May 1789 to September 1790 he traveled to Germany, Switzerland, France, England, visiting Berlin, Leipzig, Geneva, Paris, London. Returning to Moscow, he began to publish the "Moscow Journal", which at that time had a very significant success: already in the first year he had 300 "subscripts". The magazine, which did not have full-time employees and was filled by Karamzin himself, existed until December 1792. After the arrest of Novikov and the publication of the ode "To Mercy", Karamzin almost fell under investigation on suspicion that he was sent abroad by Masons. In 1793-1795 he spent most of his time in the countryside.

In 1802, Karamzin's first wife, Elizaveta Ivanovna Protasova, died. In 1802, he founded the first private literary and political journal in Russia, Vestnik Evropy, for whose editorial staff he subscribed to 12 of the best foreign journals. Karamzin attracted G.R. Derzhavin, Kheraskov, Dmitriev, V.L. Pushkin, brothers A.I. and N.I. Turgenev, A.F. Voeikova, V.A. Zhukovsky. Despite the large number of authors, Karamzin has to work a lot on his own, and so that his name does not flash before the eyes of readers so often, he invents a lot of pseudonyms. At the same time, he became a popularizer of Benjamin Franklin in Russia. Vestnik Evropy existed until 1803.

October 31, 1803, with the help of Comrade Minister of Public Education M.N. Muravyov, by decree of Emperor Alexander I, Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was appointed official historiographer with a salary of 2,000 rubles to write a complete history of Russia. In 1804 Karamzin married the natural daughter of Prince A.I. Vyazemsky Ekaterina Andreevna Kolyvanova and from that moment settled in the Moscow house of the Vyazemsky princes, where he lived until 1810. From 1804 he began work on the History of the Russian State, the compilation of which became his main occupation until the end of his life. In 1816, the first 8 volumes were published (the second edition was published in 1818-1819), in 1821 volume 9 was printed, in 1824 - volumes 10 and 11. D.N. Bludov). Thanks to its literary form, "The History of the Russian State" became popular among readers and admirers of Karamzin as a writer, but even then it was deprived of serious scientific significance. All 3,000 copies of the first edition sold out in 25 days. For the science of that time, the extensive "Notes" to the text, which contained many extracts from manuscripts, mostly published for the first time by Karamzin, were of much greater importance. Some of these manuscripts no longer exist. Karamzin received practically unlimited access to the archives of state institutions of the Russian Empire: materials were taken from the Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (colleges at that time), from the Synodal Depository, from the library of monasteries (Trinity Lavra, Volokolamsk Monastery and others), from private collections of Musin- Pushkin, Chancellor Rumyantsev and A.I. Turgenev, who compiled a collection of documents from the papal archive. Trinity, Lavrentievskaya, Ipatievskaya annals, Dvinsky letters, Code of Laws were used. Thanks to the "History of the Russian State", the readership became aware of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign", "The Teaching of Monomakh" and many other literary works of ancient Rus'. Despite this, already during the life of the writer, critical works appeared on his "History ...". The historical concept of Karamzin, who was a supporter of the Norman theory of the origin of the Russian state, became the official and supported state power. At a later time, "History ..." was positively evaluated by A.S. Pushkin, N.V. Gogol, Slavophiles, negatively - Decembrists, V.G. Belinsky, N.G. Chernyshevsky. Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was the initiator of the organization of memorials and the erection of monuments to outstanding figures of national history, one of which was the monument to K. M. Minin and D.M. Pozharsky on Red Square in Moscow.

Before the publication of the first eight volumes, Karamzin lived in Moscow, from where he traveled only in 1810 to Tver to the Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna, in order to convey to the sovereign his note "On Ancient and New Russia" through her, and to Nizhny, when the French occupied Moscow. Summer Karamzin usually spent in Ostafyevo, the estate of his father-in-law - Prince Andrei Ivanovich Vyazemsky. In August 1812, Karamzin lived in the house of the commander-in-chief of Moscow, Count F.V. Rostopchin and left Moscow a few hours before the entry of the French. As a result of the Moscow fire, Karamzin's personal library, which he had collected for a quarter of a century, perished. In June 1813, after the family returned to Moscow, he settled in the house of the publisher S.A. Selivanovsky, and then - in the house of the Moscow theater-goer F.F. Kokoshkin. In 1816, Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin moved to St. Petersburg, where he spent the last 10 years of his life and became close to the royal family, although Emperor Alexander I, who did not like criticism of his actions, treated the writer with restraint from the time the Note was submitted. Following the wishes of Empresses Maria Feodorovna and Elizaveta Alekseevna, Nikolai Mikhailovich spent the summer in Tsarskoe Selo. In 1818 Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was elected an honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. In 1824 Karamzin became a real state councilor. The death of Emperor Alexander I shocked Karamzin and undermined his health; half-ill, he visited the palace every day, talking with Empress Maria Feodorovna. In the first months of 1826, Karamzin experienced pneumonia and, on the advice of doctors, decided to go to southern France and Italy in the spring, for which Emperor Nicholas gave him money and placed a frigate at his disposal. But Karamzin was already too weak to travel, and on June 3 (according to the old style on May 22), 1826, he died in St. Petersburg.

Among the works of Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin are critical articles, reviews of literary, theatrical, historical topics, letters, stories, odes, poems: "Eugene and Julia" (1789; story), "Letters of a Russian Traveler" (1791-1795; separate edition - in 1801; letters written during a trip to Germany, Switzerland, France and England, and reflecting the life of Europe on the eve and during the French Revolution), "Liodor" (1791, story), "Poor Lisa" (1792; story; published in "Moscow Journal"), "Natalia, Boyar's Daughter" (1792; story; published in the "Moscow Journal"), "To Mercy" (ode), "Aglaya" (1794-1795; almanac), "My trinkets" (1794 ; 2nd edition - in 1797, 3rd - in 1801; a collection of articles published earlier in the "Moscow Journal"), "Pantheon of Foreign Literature" (1798; reader on foreign literature, which did not go through censorship for a long time, which forbade the printing of Demosthenes , Cicero, Sallust, because they were republicans), "Historical eulogy to Empress Catherine II" (1802), "Marfa Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod" (1803; published in Vestnik Evropy; Historical Tale), Note on Ancient and New Russia in Its Political and Civil Relations (1811; criticism of M.M. Speransky’s projects of state reforms), Note on Moscow Landmarks - a historical guide to Moscow and its environs), "A Knight of Our Time" (an autobiographical story published in Vestnik Evropy), "My Confession" (a story that denounced the secular education of the aristocracy), "The History of the Russian State" (1816-1829: vols. 1-8 - in 1816-1817, vol. 9 - in 1821, vols. 10-11 - in 1824, vol. 12 - in 1829; the first generalizing work on the history of Russia), Karamzin's letters to A.F. Malinovsky" (published in 1860), to I.I. Dmitriev (published in 1866), to N.I. Krivtsov, to Prince P.A. Vyazemsky (1810-1826; published in 1897), to A.I. Turgenev (1806 -1826; published in 1899), correspondence with Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich (published in 1906), "Historical memories and remarks on the way to the Trinity" (article), "On the Moscow earthquake of 1802" (article), "Notes of an old Moscow resident" (article), "Journey around Moscow" (article), "Russian antiquity" (article), "About the light clothes of fashionable beauties of the ninth to tenth centuries" (article).

Biography

Coming from a wealthy noble family, the son of a retired army officer.

In 1779-81 he studied at the Moscow boarding school Shaden.

In 1782-83 he served in the Preobrazhensky Guards Regiment.

In 1784/1785 he settled in Moscow, where, as an author and translator, he became close friends with the Masonic circle of the satirist and publisher N.I. Novikov.

In 1785-89 - a member of the Moscow circle of N. I. Novikov. Karamzin's Masonic mentors were I. S. Gamaleya and A. M. Kutuzov. After retiring and returning to Simbirsk, he met Freemason I. P. Turgenev.

In 1789-1790. traveled to Western Europe, where he met many prominent representatives of the Enlightenment (Kant, Herder, Wieland, Lavater, etc.). He was influenced by the ideas of the first two thinkers, as well as Voltaire and Shaftesbury.

Upon his return to his homeland, he published "Letters of a Russian Traveler" (1791-1795) with reflections on the fate of European culture and founded the "Moscow Journal" (1791-1792), a literary and artistic periodical, where he published works by contemporary Western European and Russian authors. After the accession to the throne in 1801, Emperor Alexander I undertook the publication of the journal Vestnik Evropy (1802-1803) (the motto of which was "Russia is Europe"), the first of numerous Russian literary and political review magazines, where the tasks of forming national self-consciousness were set through the assimilation by Russia of the civilizational experience of the West and, in particular, the experience of the new European philosophy (from F. Bacon and R. Descartes to I. Kant and J.-J. Rousseau).

Social progress Karamzin associated with the success of education, the development of civilization, the improvement of man. During this period, the writer, in general, being on the positions of conservative Westernism, positively assessed the principles of the theory of social contract and natural law. He was a supporter of freedom of conscience and utopian ideas in the spirit of Plato and T. More, believed that in the name of harmony and equality, citizens can give up personal freedom. As skepticism about utopian theories grew, Karamzin became more convinced of the enduring value of individual and intellectual freedom.

The story "Poor Lisa" (1792), which affirms the inherent value of the human person as such, regardless of class, brought Karamzin immediate recognition. In the 1790s, he was the head of Russian sentimentalism, as well as the inspirer of the movement to emancipate Russian prose, which was stylistically dependent on the Church Slavonic liturgical language. Gradually, his interests moved from the field of literature to the field of history. In 1804, he resigned as editor of the journal, accepted the position of imperial historiographer, and until his death was occupied almost exclusively with composing The History of the Russian State, the first volume of which appeared in print in 1816. In 1810–1811, Karamzin, on the personal order of Alexander I, compiled ancient and new Russia”, where, from the conservative positions of the Moscow nobility, he sharply criticized domestic and foreign Russian policy. Karamzin died in St. Petersburg on May 22 (June 3), 1826.

K. called for the development of the European philosophical heritage in all its diversity - from R. Descartes to I. Kant and from F. Bacon to K. Helvetius.

In social philosophy, he was an admirer of J. Locke and J. J. Rousseau. He adhered to the conviction that philosophy, having got rid of scholastic dogmatism and speculative metaphysics, is capable of being "the science of nature and man." A supporter of experiential knowledge (experience is the "gatekeeper of wisdom"), he also believed in the power of the mind, in the creative potential of the human genius. Speaking against philosophical pessimism and agnosticism, he believed that errors in science are possible, but they "are, so to speak, growths alien to it." In general, he is characterized by religious and philosophical tolerance for other views: "For me, he is a true philosopher who can get along with everyone in the world; who loves those who disagree with his way of thinking."

A person is a social being (“we are born for society”), capable of communicating with others (“our “I” sees itself only in another “you”), therefore, to intellectual and moral improvement.

History, according to K., testifies that "the human race rises to spiritual perfection." The golden age of mankind is not behind, as Rousseau claimed, who deified the ignorant savage, but ahead. T. Mor in his "Utopia" foresaw a lot, but still it is "a dream of a kind heart."

K. assigned an important role in the improvement of human nature to art, which indicates to a person worthy ways and means of achieving happiness, as well as forms of reasonable enjoyment of life - through the elevation of the soul ("Something about the sciences, arts and enlightenment").

Watching the events of 1789 in Paris, listening to the speeches of O. Mirabeau in the Convention, talking with J. Condorcet and A. Lavoisier (it is possible that Karamzin visited M. Robespierre), plunging into the atmosphere of the revolution, he hailed it as a "victory of reason". However, he later condemned sans-culottism and the Jacobin terror as a collapse of the ideas of the Enlightenment.

In the ideas of the Enlightenment, Karamzin saw the final overcoming of the dogmatism and scholasticism of the Middle Ages. Critically evaluating the extremes of empiricism and rationalism, he, at the same time, emphasized the cognitive value of each of these directions and resolutely rejected agnosticism and skepticism.

Upon returning from Europe, K. rethinks his philosophical and historical creed and turns to the problems of historical knowledge, the methodology of history. In the "Letters of Melodorus and Philaletus" (1795), he discusses the fundamental solutions of two concepts of the philosophy of history - the theory of the historical cycle, coming from G. Vico, and the steady social ascent of mankind (progress) to the highest goal, to humanism, originating from I. G. Herder, whom he valued for his interest in the language and history of the Slavs, casts doubt on the idea of automatic progress and comes to the conclusion that the hope for the steady progress of mankind is more shaky than it seemed to him before.

History appears to him as "an eternal mixture of truths with errors and virtue with vice", "softening of morals, progress of reason and feelings", "spreading the spirit of society", as only a distant prospect of mankind.

Initially, the writer was characterized by historical optimism and faith in the inevitability of social and spiritual progress, but since the late 1790s. Karamzin connects the development of society with the will of Providence. Since that time, philosophical skepticism has been characteristic of him. The writer is more and more inclined towards rational providentialism, seeking to reconcile it with the recognition of the free will of man.

Developing the idea of the unity of the historical path of Russia and Europe from a humanistic position, Karamzin at the same time gradually became convinced of the existence of a special path of development for each people, which led him to the idea of substantiating this position on the example of the history of Russia.

At the very beginning 19th century (1804) he embarks on the work of his whole life - a systematic work in Russian. history, collecting materials, examining archives, collating chronicles.

Karamzin brought the historical narrative to the beginning of the 17th century, while he used many primary sources that had previously been overlooked (some have not reached us), and he managed to create an interesting story about the past of Russia.

The methodology of historical research was developed by him in his previous works, in particular in "The Reasoning of a Philosopher, Historian and Citizen" (1795), as well as in "A Note on Ancient and New Russia" (1810-1811). A reasonable interpretation of history, he believed, is based on respect for the sources (in Russian historiography - on a conscientious study, first of all, of the annals), but does not come down to a simple transcription of them.

"The historian is not a chronicler." It should stand on the basis of explaining the actions and psychology of the subjects of history, pursuing their own and class interests. The historian is obliged to strive to understand the internal logic of the events taking place, to single out the most significant and important in the events, describing them, "should rejoice and grieve with his people. He must not, guided by predilection, distort facts, exaggerate or belittle in his presentation of the disaster; he must above all, be truthful.

The main ideas of Karamzin from the "History of the Russian State" (the book was published in 11 volumes in 1816-1824, the last - 12 volumes - in 1829 after the death of the author) can be called conservative - monarchical. They realized the conservative-monarchical convictions of Karamzin as a historian, his providentialism and ethical determinism as a thinker, his traditional religious and moral consciousness. Karamzin focuses on the national characteristics of Russia, first of all, it is autocracy, free from despotic extremes, where the sovereign must be guided by the law of God and conscience.

He saw the historical purpose of the Russian autocracy in maintaining public order and stability. From a paternalistic position, the writer justified serfdom and social inequality in Russia.

Autocracy, according to Karamzin, being an extra-class power, is the “palladium” (guardian) of Russia, the guarantor of the unity and well-being of the people. The strength of autocratic rule is not in formal law and legality according to the Western model, but in conscience, in the “heart” of the monarch.

This is paternal rule. The autocracy must unswervingly follow the rules of such a government, while the postulates of the government are as follows: "Every news in the state order is an evil, to which one must resort only when necessary." "We demand more protective wisdom than creative wisdom." "For the firmness of being a state, it is safer to enslave people than to give them freedom at the wrong time."

True patriotism, K. believed, obliges a citizen to love his fatherland, despite his delusion and imperfections. Cosmopolitan, according to K., "a metaphysical being."

Karamzin occupied an important place in the history of Russian culture due to the circumstances that were fortunate for him, as well as his personal charm and erudition. A true representative of the age of Catherine the Great, he combined Westernism and liberal aspirations with political conservatism. The historical self-consciousness of the Russian people owes much to Karamzin. Pushkin noted this by saying that "Ancient Russia seemed to be found by Karamzin, like America by Colomb."

Among the works of Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin are critical articles and reviews on literary, theatrical, historical topics;

Letters, stories, odes, poems:

* "Eugene and Julia" (1789; story),

* "Letters of a Russian Traveler" (1791-1795; separate edition - in 1801;

* letters written during a trip to Germany, Switzerland, France and England, and reflecting the life of Europe on the eve and during the French Revolution),

* "Liodor" (1791, story),

* "Poor Lisa" (1792; story; published in the "Moscow Journal"),

* "Natalya, the boyar's daughter" (1792; story; published in the "Moscow Journal"),

* "To mercy" (ode),

* "Aglaya" (1794-1795; almanac),

* "My trinkets" (1794; 2nd edition - in 1797, 3rd - in 1801; a collection of articles published earlier in the "Moscow Journal"),

* "Pantheon of Foreign Literature" (1798; an anthology on foreign literature, which did not go through censorship for a long time, which forbade the publication of Demosthenes, Cicero, Sallust, since they were republicans).

Historical and literary works:

* "Historical eulogy to Empress Catherine II" (1802),

* "Marfa Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod" (1803; published in the "Bulletin of Europe; historical story"),

* "A note on ancient and new Russia in its political and civil relations" (1811; criticism of the projects of state reforms by M.M. Speransky),

* "Note on Moscow Landmarks" (1818; the first cultural and historical guide to Moscow and its environs),

* "Knight of Our Time" (story-autobiography published in "Bulletin of Europe"),

* "My Confession" (a story that denounced the secular education of the aristocracy),

* "History of the Russian State" (1816-1829: v. 1-8 - in 1816-1817, v. 9 - in 1821, v. 10-11 - in 1824, v. 12 - in 1829; the first generalizing work on history Russia).

Letters:

* Letters from Karamzin to A.F. Malinovsky" (published in 1860),

* to I.I. Dmitriev (published in 1866),

* to N.I. Krivtsov,

* to Prince P.A. Vyazemsky (1810-1826; published in 1897),

* to A.I. Turgenev (1806-1826; published in 1899),

* Correspondence with Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich (published in 1906).

Articles:

* "Historical memories and remarks on the way to the Trinity" (article),

* "On the Moscow earthquake of 1802" (article),

* "Notes of an old Moscow resident" (article),

* "Journey around Moscow" (article),

* "Russian antiquity" (article),

* "About the light clothing of fashionable beauties of the ninth - tenth century" (article).

Sources:

* Ermakova T. Karamzin Nikolai Mikhailovich [Text] / T. Ermakova// Philosophical Encyclopedia: in 5 volumes. V.2.: Disjunction - Comic / Institute of Philosophy of the USSR Academy of Sciences; scientific council: A.P. Alexandrov [and others]. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia, 1962. - S. 456;

* Malinin V. A. Karamzin Nikolai Mikhailovich [Text] / V. A. Malinin // Russian Philosophy: Dictionary / ed. ed. M. A. Maslina - M.: Respublika, 1995. - S. 217 - 218.

* Khudushina I.F. Karamzin Nikolai Mikhailovich [Text] / I.F. Khudushina // New Philosophical Encyclopedia: in 4 volumes. T.2 .: E - M / Institute of Philosophy Ros. acad. Sciences, National societies. - scientific fund; scientific-ed. advice: V. S. Stepin [and others]. - M.: Thought, 2001. - P. 217 - 218;

Bibliography

Compositions:

* Essays. T.1-9. - 4th ed. - St. Petersburg, 1834-1835;

* Translations. T.1-9. - 3rd ed. - St. Petersburg, 1835;

* Letters from N. M. Karamzin to I. I. Dmitriev. - St. Petersburg, 1866;

* Something about the sciences, arts and enlightenment. - Odessa, 1880;.

* Letters from a Russian traveller. - L., 1987;

* A note about ancient and new Russia. - M., 1991.

* History of the Russian state, vol. 1-4. - M, 1993;

Literature:

* Platonov S. F. N. M. Karamzin ... - St. Petersburg, 1912;

* Essays on the history of historical science in the USSR. T. 1. - M., 1955. - S. 277 - 87;

* Essays on the history of Russian journalism and criticism. T. 1. Ch. 5. -L., 1950;

* Belinsky V.G. Works of Alexander Pushkin. Art. 2. // Complete Works. T. 7. - M., 1955;

* Pogodin M.P. N.M. Karamzin, according to his writings, letters and reviews of contemporaries. Ch. 1-2. - M., 1866;

* [Gukovsky G.A.] Karamzin // History of Russian Literature. T. 5. - M. - L., 1941. - S. 55-105;

* Lekabrists-critics of the "History of the Russian State" N.M. Karamzin // Literary heritage. T. 59. - M., 1954;

* Lotman Yu. The evolution of Karamzin's worldview // Scientific Notes of the Tartu State University. - 1957. - Issue. 51. - (Proceedings of the Faculty of History and Philology);

* Mordovchenko N.I. Russian criticism of the first quarter of the 19th century. - M. - L., 1959. - S.17-56;

* Storm G.P. New about Pushkin and Karamzin // Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Dep. literature and language. - 1960. - T. 19. - Issue. 2;

* Predtechensky A.V. Socio-political views of N.M. Karamzin in the 1790s // Problems of Russian education in the literature of the 18th century - M.-L., 1961;

* Makogonenko G. Karamzin's literary position in the 19th century, “Rus. Literature”, 1962, No. 1, p. 68-106;

* History of Philosophy in the USSR. T. 2. - M., 1968. - S. 154-157;

* Kislyagina L. G. Formation of socio-political views of N. M. Karamzin (1785-1803). - M., 1976;

* Lotman Yu. M. Karamzin. - M., 1997.

* Wedel E. Radiśćev und Karamzin // Die Welt der Slaven. - 1959. - H. 1;

* Rothe H. Karamzin-studien // Z. slavische Philologie. - 1960. - Bd 29. - H. 1;

* Wissemann H. Wandlungen des Naturgefühls in der neuren russischen Literatur // ibid. - Bd 28. - H. 2.

Archives:

* RO IRLI, f. 93; RGALI, f. 248; RGIA, f. 951; OR RSL, f. 178; RORNB, f. 336.

Biography (Catholic Encyclopedia. Edwart. 2011, K. Yablokov)

He grew up in the village of his father, a Simbirsk landowner. He received his primary education at home. In 1773-76 he studied in Simbirsk at the boarding house Fauvel, then in 1780-83 - at the boarding house of prof. Moscow University of Schaden in Moscow. During his studies, he also attended lectures at Moscow University. In 1781 he entered the service of the Preobrazhensky Regiment. In 1785, after his resignation, he became close to the Masonic circle of N.I. Novikov. During this period, the formation of the worldview and lit. K.'s views were greatly influenced by the philosophy of the Enlightenment, as well as the work of English. and German. sentimental writers. First lit. experience K. associated with the magazine Novikov Children's reading for the heart and mind, where in 1787-90 he published his numerous. translations, as well as the story of Eugene and Julia (1789).

In 1789 K. broke with the Masons. In 1789-90 he traveled to the West. Europe, visited Germany, Switzerland, France and England, met with I. Kant and I.G. Herder. The impressions of the trip became the basis of his Op. Letters from a Russian traveler (1791-92), in which, in particular, K. expressed his attitude to the French Revolution, which he considered one of the key events of the 18th century. The period of the Jacobin dictatorship (1793-94) disappointed him, and in the reprint of Letters ... (1801) the story of the events of Franz. K. accompanied the revolution with a comment about the disastrous for the state of any violent upheavals.

After returning to Russia, K. published the Moscow Journal, in which he also published his own artists. works (the main part of the Letters of a Russian traveler, the stories of Liodor, Poor Liza, Natalya, the boyar daughter, poems Poetry, To Mercy, etc.), as well as critical. articles and lit. and theater reviews, promoting the aesthetic principles of Russian. sentimentalism.

After a forced silence in the reign of imp. Paul I K. again acted as a publicist, substantiating the program of moderate conservatism in the new journal Vestnik Evropy. Here was published his ist. the story of Martha Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod (1803), which asserted the inevitability of the victory of the autocracy over the free city.

Lit. activity K. played a big role in the improvement of art. means of the image vnutr. world of man, in the development of Russian. lit. language. In particular, K.'s early prose influenced V.A. Zhukovsky, K.N. Batyushkov, young A.S. Pushkin.

From Ser. In 1790, K.'s interest in the problems of the methodology of history was determined. One of the main theses K .: "The historian is not a chronicler", he must strive to understand the internal. logic of ongoing events, must be "truthful", and no predilections and ideas can serve as an excuse for distorting the source. facts.

In 1803, K. was appointed court historiographer, after which he began work on his chapter. work - the History of the Russian State (vols. 1-8, 1816-17; vol. 9, 1821; vol. 10-11, 1824; vol. 12, 1829), which became not only a significant source. labor, but also a major phenomenon in Russian. artistic prose and the most important source for Russian. ist. dramaturgy, starting with Pushkin's Boris Godunov.

When working on the History of the Russian state, K. used not only almost all the lists of Russian available in his time. Chronicles (more than 200) and ed. ancient Russian monuments. law and literature, but also numerous. handwritten and printed Western Europe. sources. A story about each period of Russian history. state-va is accompanied by many references and quotations from Op. European authors, and not only those who wrote about Russia proper (like Herberstein or Kozma of Prague), but also other historians, geographers, and chroniclers (from the ancients to contemporaries of K.). In addition, History ... contains many important Russian. a reader of information on the history of the Church (from the Church Fathers to the Church Annals of Barony), as well as quotations from papal bulls and other documents of the Holy See. One of the main concepts of the work of K. was the criticism of East. sources in accordance with the methods of Enlightenment historians. History ... K. contributed to an increase in interest in national history in various layers of Russian. society. East the concept of K. became official. concept supported by the state. power.

K.'s views, expressed in the History of the Russian State, are based on a rationalistic conception of the course of societies. development: the history of mankind is the history of world progress, the basis of which is the struggle of reason with delusion, of enlightenment with ignorance. Ch. driving force ist. K. considered the process of power, the state, identifying the history of the country with the history of the state, and the history of the state - with the history of autocracy.

The decisive role in history, according to K., is played by individuals (“History is the sacred book of kings and peoples”). Psychological analysis of actions ist. personaly is for K. osn. method of explanation. events. The purpose of history, according to K., is to regulate societies. and cult. people's activities. Ch. the institute for maintaining order in Russia is autocracy, the strengthening of monarchical power in the state allows you to save the cult. and ist. values. The Church must interact with the government, but not obey it, because. this leads to a weakening of the authority of the Church and faith in the state-ve, and the devaluation of rel. values - to the destruction of in-that monarchy. The spheres of activity of the state and the Church, in the understanding of K., cannot intersect, but in order to preserve the unity of the state, their efforts must be combined.

K. was a supporter of rel. tolerance, however, in his opinion, each country should adhere to the chosen religion, therefore in Russia it is important to preserve and support the Orthodox Church. Church. K. considered the Catholic Church as a constant enemy of Russia, who sought to “implant” a new faith. In his opinion, contacts with the Catholic Church only harmed the cult. identity of Russia. K. subjected the Jesuits to the greatest criticism, in particular for their interference in the internal. Russian policy during the Time of Troubles early. 17th century

In 1810-11, K. compiled a Note on Ancient and New Russia, where he criticized the interior from a conservative position. and ext. grew up policy, in particular the state projects. transformations M.M. Speransky. In the Note ... K. moved away from his original views on the East. development of mankind, arguing that there is a special path of development characteristic of each nation.

Cit.: Works. St. Petersburg, 1848. 3 volumes; Works. L., 1984. 2 volumes; Complete collection of poems. M.-L., 1966; History of Russian Goverment. SPb., 1842-44. 4 books; Letters from a Russian traveler. L., 1984; History of Russian Goverment. M., 1989-98. 6 volumes (ed. not completed); A note about ancient and new Russia in its political and civil relations. M., 1991.

Lit-ra: Pogodin M.P. Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin based on his writings, letters and reviews of contemporaries. M., 1866. 2 hours; Eidelman N.Ya. The last chronicler. M., 1983; Osetrov E.I. Three lives of Karamzin. M., 1985; Vatsuro V.E., Gilelson M.I. Through "mental dams". M., 1986; Kozlov V.P. "History of the Russian State" N.M. Karamzin in the assessments of contemporaries. M., 1989; Lotman Yu.M. Creation of Karamzin. M., 1997.

On some of Pushkin's references to journalism and prose by N.M. Karamzin (L.A. Mesenyashin (Chelyabinsk))

Speaking about the contribution of N.M. Karamzin to Russian culture, Yu.M. Lotman notes that, among other things, N.M. Karamzin created "two more important figures in the history of culture: the Russian Reader and the Russian Reader" [Lotman, Yu.M. The Creation of Karamzin [Text] / Yu.M. Lotman. - M .: Book, 1987. S. 316]. At the same time, when we turn to such a textbook Russian reading as “Eugene Onegin”, it sometimes becomes noticeable that the modern Russian reader lacks precisely “reader qualifications”. It is primarily about the ability to see the intertextual connections of the novel. The importance of the role of "alien words" in the novel "Eugene Onegin" was pointed out by almost all researchers of Pushkin's work. Yu.M. Lotman, who gave a detailed classification of the forms of representation of "alien speech" in "Eugene Onegin", notes, with reference to the works of Z.G. Mintz, G. Levinton, and others that "quotes and reminiscences constitute one of the main structure-forming elements in the very fabric of the narrative of the novel in Pushkin's verses" [Lotman, Yu.M. Roman A.S. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin" [Text] / Yu.M. Lotman // Lotman, Yu.M. Pushkin. - St. Petersburg: Art-SPB, 1995. S. 414]. Among the diverse functions of the quotation Yu.M. Lotman pays special attention to the so-called. "hidden quotations", the selection of which "is achieved not by means of graphics and typographic signs, but by identifying some places in the text of Onegin with texts stored in the memory of readers" [Ibid.]. Such “hidden quotes”, in the language of modern advertising theory, carry out “audience segmentation”, with a “multi-stage system of approaching the reader to the text” [Ibid.]. And further: "... Quotations, actualizing certain extra-textual connections, create a certain "image of the audience" of this text, which indirectly characterizes the text itself" [Ibid., p. 416]. The abundance of proper names (Yu.M. Lotman has about 150 of them) of “poets, artists, cultural figures, politicians, historical characters, as well as the names of works of art and the names of literary heroes” (ibid.) turns the novel, in a sense, into a secular a conversation about common acquaintances ("Onegin -" my good friend ").

Yu.M. Lotman pays attention to the echo of Pushkin's novel with the texts of N.M. Karamzin, pointing out, in particular, that the situation from N.M. Karamzin [Lotman, Yu.M. Roman A.S. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin" [Text] / Yu.M. Lotman // Lotman, Yu.M. Pushkin. - St. Petersburg: Art-SPB, 1995. S. 391 - 762]. Moreover, in this context, it turns out to be surprising that the researchers did not notice yet another “hidden quote”, more precisely, an allusion in the XXX stanza of the second chapter of “Eugene Onegin”. Under the allusion, following A.S. Evseev, we will understand “a reference to a previously known fact (protosystem) taken in its singularity, accompanied by a paradigmatic increment of a metasystem” (a semiotic system containing a representative of allusion) [Evseev, A.S. Fundamentals of the theory of allusion [Text]: author. dis. …cand. philol. Sciences: 10.02.01/ Evseev Alexander Sergeevich. - Moscow, 1990. S. 3].

Recall that, characterizing the well-known liberalism of Tatyana's parents in relation to the circle of her reading, Pushkin motivated him, in particular, by the fact that Tatyana's mother "was crazy about Richardson herself." And then comes the textbook:

"She loved Richardson

Not because I read

Not because Grandison

She preferred Lovlace ... "

A.S. himself Pushkin, in a note to these lines, points out: “Grandison and Lovlas, the heroes of two glorious novels” [Pushkin, A.S. Selected works [Text]: in 2 volumes / A.S. Pushkin. - M .: Fiction, 1980. - V.2. S. 154]. In Yu. M. Lotman’s “Comments on the novel “Eugene Onegin”, which has become no less textbook, in the notes to this stanza, in addition to the above Pushkin’s note, the following is added: “The first is the hero of impeccable virtue, the second is of insidious, but charming evil. Their names have become household names” [Lotman, Yu.M. Roman A.S. Pushkin "Eugene Onegin" [Text] / Yu.M. Lotman // Lotman, Yu.M. Pushkin. - St. Petersburg: Art-SPB, 1995. S. 605].

The stinginess of such a commentary would be quite justified if one could forget about the “segmenting role” of allusions in this novel. According to Yu.M. Lotman, from among those readers who can "correlate the quotation contained in Pushkin's text with a certain external text and extract the meanings arising from this comparison" [Ibid. P. 414], only the narrowest, most friendly circle knows the “domestic semantics” of this or that quotation.

For a correct understanding of this quatrain, Pushkin's contemporaries did not at all need to enter the narrowest circle. It was enough to coincide with him in terms of reading, and for this it was enough to be familiar with the texts of "Richardson and Rousseau", firstly, and N.M. Karamzin, secondly. Because anyone for whom these conditions are met will easily notice in this quatrain a polemical, but almost verbatim citation of a fragment of the Letters of a Russian Traveler. So, in a letter marked "London, July ... 1790" N.M. Karamzin describes a certain girl Jenny, a servant in the rooms where the hero of Letters stayed, who managed to tell him the “secret story of her heart”: “At eight o’clock in the morning she brings me tea with crackers and talks to me about Fielding and Richardson novels. She has a strange taste: for example, Lovelace seems to her incomparably nicer than Grandison. Such are London maids!” [Karamzin, N.M. Knight of our time [Text]: Poetry, prose. Publicism / N.M. Karamzin. - M. : Parad, 2007. S. 520].

Another significant circumstance indicates that this is not an accidental coincidence. Recall that this quatrain in Pushkin is preceded by the stanza

“She [Tatiana] liked novels early on;

They replaced everything…”

For our contemporaries, this characteristic means only the heroine's quite commendable love for reading. Meanwhile, Pushkin emphasizes that this is not a love for reading in general, but for reading novels in particular, which is not the same thing. The fact that the love of reading novels on the part of a young noble maiden is by no means an unambiguously positive characteristic is evidenced by a very characteristic passage from the article by N.M. Karamzin “On the book trade and love of reading in Russia” (1802): “It is in vain to think that novels can be harmful to the heart…” [Ibid. P. 769], “In a word, it’s good that our public reads novels too!” [Ibid. S. 770]. The very need for this kind of argumentation testifies to the presence in public opinion of a directly opposite belief, and it is not unreasonable, given the subject matter and the very language of European novels of the Enlightenment. Indeed, even with the most ardent defense of N.M. Karamzin nowhere claims that this reading is the most suitable for young girls, because the "Enlightenment" of the latter in some areas, at least in the eyes of Russian society of that time, bordered on outright corruption. And the fact that Pushkin calls the next volume of the novel under Tatyana's pillow "secret" is not accidental.

True, Pushkin emphasizes that there was no need for Tatyana to hide the “secret volume”, since her father, “a simple and kind gentleman”, “considered books an empty toy”, and his wife, despite all her previous claims, and as a girl I read less than an English maid.

Thus, the discovery of Karamzin's lines, to which the XXX Pushkin stanza refers us, adds a new bright shade to the understanding of this novel as a whole. We are becoming more understandable and the image of the "enlightened Russian lady" in general and the author's attitude towards him in particular. In this context, the image of Tatyana also receives new colors. If Tatyana grows up in such a family, then this is really an outstanding personality. And on the other hand, it is in such a family that an “enlightened” (too enlightened?) young lady can remain a “Russian soul”. It immediately becomes clear to us that the lines from her letter: “Imagine: I’m alone here ...” is not only a romantic cliche, but also a harsh reality, and the letter itself is not only a willingness to follow romantic precedents, but also a desperate act aimed at finding a close soul OUTSIDE the circle outlined by a predetermined pattern.

So, we see that Pushkin's novel is a truly integral artistic system, each element of it "works" for the final idea, the intertextuality of the novel is the most important component of this system, and that is why one should not lose sight of any of the intertextual connections of the novel. At the same time, the risk of losing the understanding of these relations increases as the time gap between the author and the reader increases, so restoring the intertextuality of Pushkin's novel remains an urgent task.

Biography (K.V. Ryzhov)

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was born in December 1766 in the village of Mikhailovka, Simbirsk province, into the family of a middle-class nobleman. He was educated at home and in private boarding schools. In 1783, young Karamzin went to St. Petersburg, where for some time he served as a lieutenant in the Preobrazhensky Guards Regiment. Military service, however, did not fascinate him much. In 1784, having learned about the death of his father, he retired, settled in Moscow and plunged headlong into literary life. Its center at that time was the famous book publisher Novikov. Despite his youth, Karamzin soon became one of his most active collaborators and worked hard on translations.

Constantly reading and translating European classics, Karamzin passionately dreamed of visiting Europe himself. His wish came true in 1789. Having saved up money, he went abroad and traveled around different countries for almost a year and a half. This pilgrimage to the cultural centers of Europe was of great importance in the formation of Karamzin as a writer. He returned to Moscow with many plans. First of all, he founded the "Moscow Journal", with the help of which he intended to acquaint compatriots with Russian and foreign literature, instilling a taste for the best examples of poetry and prose, present "critical reviews" of published books, report on theater premieres and everything else related to literary life in Russia and Europe. The first issue was published in January 1791. It contained the beginning of the "Letters of a Russian Traveler", written on the basis of the impressions of a trip abroad and representing an interesting travel diary, in the form of letters to friends. This work was a huge success with the reading public, which admired not only the fascinating description of the life of European peoples, but also the light, pleasant style of the author. Before Karamzin, a firm belief was widespread in Russian society that books were written and printed for "scientists" alone, and therefore their content should be as important and sensible as possible. In fact, this led to the fact that the prose turned out to be heavy and boring, and its language - cumbersome and eloquent. In fiction, many Old Slavonic words, which had long since fallen into disuse, continued to be used. Karamzin was the first Russian prose writer to change the tone of his works from solemn and instructive to sincerely disposing. He also completely abandoned the pompous artsy style and began to use a lively and natural language, close to colloquial speech. Instead of dense Slavicisms, he boldly introduced into literary circulation many new borrowed words, which had previously been used only in oral speech by European-educated people. It was a reform of great importance - one might say that our modern literary language was first born on the pages of Karamzin's journal. Coherently and interestingly written, it successfully instilled a taste for reading and became the publication around which the reading public united for the first time. The Moscow Journal became a significant phenomenon for many other reasons. In addition to his own works and the works of famous Russian writers, in addition to a critical analysis of works that were on everyone's lips, Karamzin included extensive and detailed articles on famous European classics: Shakespeare, Lessing, Boileau, Thomas More, Goldoni, Voltaire, Stern, Richardson . He also became the founder of theater criticism. Reviews of plays, productions, acting - all this was an unheard-of innovation in Russian periodicals. According to Belinsky, Karamzin was the first to give the Russian public a truly magazine reading. Moreover, everywhere and in everything he was not only a transformer, but also a creator.

In the following issues of the journal, in addition to Letters, articles and translations, Karamzin published several of his poems, and in the July issue he published the story Poor Lisa. This small essay, which occupied only a few pages, was a real discovery for our young literature and was the first recognized work of Russian sentimentalism. The life of the human heart, for the first time so vividly unfolded before the readers, was for many of them a stunning revelation. A simple, and in general, uncomplicated love story of a simple girl for a rich and frivolous nobleman, which ended in her tragic death, literally shocked her contemporaries, who read to her to oblivion. Looking from the height of our current literary experience, after Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Turgenev, we, of course, cannot but see many shortcomings of this story - its pretentiousness, excessive exaltation, tearfulness. However, it is important to note that it was here, for the first time in Russian literature, that the discovery of the spiritual world of man took place. It was still a timid, vague and naive world, but it arose, and the whole further course of our literature went in the direction of comprehending it. Karamzin's innovation also manifested itself in another area: in 1792 he published one of the first Russian historical novels, Natalya, the Boyar's Daughter, which serves as a bridge from Letters of a Russian Traveler and Poor Lisa to Karamzin's later works - Marfa Posadnitsa" and "History of the Russian State". The plot of "Natalia", unfolding against the backdrop of the historical situation of the times of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, is distinguished by romantic poignancy. Everything is here - sudden love, a secret wedding, flight, search, return and a happy life to the grave.

In 1792, Karamzin stopped publishing the magazine and left Moscow for the countryside. Again, he returned to journalism only in 1802, when he began to publish Vestnik Evropy. From the very first issues, this magazine became the most popular periodical in Russia. The number of his subscribers in a few months exceeded 1000 people - at that time the figure was very impressive. The range of issues covered in the journal was very significant. In addition to literary and historical articles, Karamzin placed in his Vestnik political reviews, various information, messages from the field of science, art and education, as well as entertaining works of fine literature. In 1803, he published in it his best historical story "Marfa Posadnitsa, or the Conquest of Novgorod", which told about the great drama of the city humbled by the Russian autocracy, about liberty and disobedience, about a strong and powerful woman, whose greatness manifested itself in the most difficult days of her life . In this work, Karamzin's creative manner reached classical maturity. The style of "Marfa" is clear, restrained, strict. There is not even a trace of tearfulness and tenderness of "Poor Lisa". The speeches of the heroes are full of dignity and simplicity, their every word is weighty and significant. It is also important to emphasize that Russian antiquity was no longer just a background here, as in Natalya, but it itself was an object of reflection and image. It was evident that the author had been thoughtfully studying history for many years and deeply felt its tragic, contradictory course.

In fact, from many letters and references to Karamzin, it is known that at the turn of the century, Russian antiquity increasingly dragged him into its depths. He enthusiastically read chronicles and ancient acts, took out and studied rare manuscripts. In the autumn of 1803, Karamzin finally came to the decision to take on a great burden - to take up writing a work on national history. This task is long overdue. By the beginning of the XIX century. Russia remained perhaps the only European country that still did not have a complete printed and public presentation of its history. Of course, there were chronicles, but only specialists could read them. In addition, most of the chronicle lists remained unpublished. In the same way, many historical documents scattered in archives and private collections remained outside the scope of scientific circulation and were completely inaccessible not only to the reading public, but also to historians. Karamzin had to put together all this complex and heterogeneous material, critically comprehend it and present it in an easy modern language. Realizing well that the conceived business would require many years of research and full concentration, he asked for financial support from the emperor. In October 1803, Alexander I appointed Karamzin to the post of historiographer specially created for him, which gave him free access to all Russian archives and libraries. By the same decree, he was entitled to an annual pension of two thousand rubles. Although Vestnik Evropy gave Karamzin three times as much, he said goodbye to him without hesitation and devoted himself entirely to work on his History of the Russian State. According to Prince Vyazemsky, from that time on he "took the vows of historians." Secular communication was over: Karamzin stopped appearing in the living rooms and got rid of many not devoid of pleasantness, but annoying acquaintances. His life now proceeded in libraries, among shelves and racks. Karamzin treated his work with the greatest conscientiousness. He made mountains of extracts, read catalogs, looked through books and sent letters of inquiry to all corners of the world. The amount of material raised and reviewed by him was enormous. It can be said with confidence that no one before Karamzin has ever plunged so deeply into the spirit and elements of Russian history.

The goal set by the historian was complex and in many respects contradictory. He was not just to write an extensive scientific essay, painstakingly researching each era under consideration, his goal was to create a national, socially significant essay that would not require special preparation for its understanding. In other words, it was not supposed to be a dry monograph, but a highly artistic literary work intended for the general public. Karamzin worked a lot on the style and style of "History", on the artistic processing of images. Without adding anything to the documents he forwarded, he brightened up their dryness with his ardent emotional comments. As a result, a bright and juicy work came out from under his pen, which could not leave any reader indifferent. Karamzin himself once called his work a "historical poem". And in fact, in terms of the strength of the style, the amusingness of the story, the sonority of the language, this is undoubtedly the best creation of Russian prose of the first quarter of the 19th century.

But with all this, the "History" remained in the full sense of the "historical" work, although this was achieved at the expense of its overall harmony. The desire to combine the ease of presentation with its thoroughness forced Karamzin to supply almost every sentence with a special note. In these notes, he "hid" a huge number of extensive extracts, quotations from sources, retellings of documents, his polemics with the writings of his predecessors. As a result, the "Notes" were actually equal in length to the main text. The author himself was well aware of the abnormality of this. In the preface, he admitted: “The many notes and extracts I made frighten me myself ...” But he could not come up with any other way to acquaint the reader with a mass of valuable historical material. Thus, Karamzin's "History" is, as it were, divided into two parts - "artistic", intended for easy reading, and "scientific" - for a thoughtful and in-depth study of history.

Work on the "History of the Russian State" took without a trace the last 23 years of Karamzin's life. In 1816 he took the first eight volumes of his work to St. Petersburg. In the spring of 1817, "History" began to be printed at once in three printing houses - military, Senate and medical. However, editing the proofs took a lot of time. The first eight volumes appeared on sale only at the beginning of 1818 and generated an unheard-of excitement. None of Karamzin's works before had such a stunning success. At the end of February, the first edition was already sold out. “Everyone,” Pushkin recalled, “even secular women, rushed to read the history of their fatherland, hitherto unknown to them. She was a new discovery for them. Ancient Russia seemed to have been found by Karamzin, just as America was found by Columbus. For some time they didn’t talk about anything else ... "

Since that time, each new volume of the "History" has become a social and cultural event. The ninth volume, devoted to the description of the era of Ivan the Terrible, was published in 1821 and made a deafening impression on his contemporaries. The tyranny of the cruel tsar and the horrors of the oprichnina were described here with such epic power that readers simply could not find words to express their feelings. The famous poet and future Decembrist Kondraty Ryleev wrote in one of his letters: “Well, Grozny! Well, Karamzin! I don’t know what is more surprising, whether the tyranny of John or the talent of our Tacitus. The 10th and 11th volumes appeared in 1824. The era of turmoil described in them, in connection with the recent French invasion and the fire of Moscow, was extremely interesting for both Karamzin himself and his contemporaries. Many, not without reason, found this part of the "History" especially successful and strong. The last 12th volume (the author was going to end his "History" with the accession of Mikhail Romanov) Karamzin wrote already seriously ill. He didn't have time to finish it.

The great writer and historian died in May 1826.

Biography (en.wikipedia.org)

Honorary member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences (1818), full member of the Imperial Russian Academy (1818). The creator of the "History of the Russian State" (volumes 1-12, 1803-1826) - one of the first generalizing works on the history of Russia. Editor of the Moscow Journal (1791-1792) and Vestnik Evropy (1802-1803).

Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin was born on December 1 (12), 1766 near Simbirsk. He grew up in the estate of his father - retired captain Mikhail Egorovich Karamzin (1724-1783), a middle-class Simbirsk nobleman. Received home education. In 1778 he was sent to Moscow to the boarding house of Professor of Moscow University I. M. Shaden. At the same time, in 1781-1782, he attended lectures by I. G. Schwartz at the University.

Carier start

In 1783, at the insistence of his father, he entered the service in the St. Petersburg Guards Regiment, but soon retired. By the time of military service are the first literary experiments. After his resignation, he lived for some time in Simbirsk, and then in Moscow. During his stay in Simbirsk, he joined the Masonic Lodge of the Golden Crown, and after arriving in Moscow for four years (1785-1789) he was a member of the Friendly Learned Society.

In Moscow, Karamzin met writers and writers: N. I. Novikov, A. M. Kutuzov, A. A. Petrov, participated in the publication of the first Russian magazine for children - “Children's Reading for the Heart and Mind”.

Trip to Europe In 1789-1790 he made a trip to Europe, during which he visited Immanuel Kant in Königsberg, was in Paris during the great French revolution. As a result of this trip, the famous Letters of a Russian Traveler were written, the publication of which immediately made Karamzin a famous writer. Some philologists believe that modern Russian literature starts from this book. Since then, he has been considered one of its main figures.

Return and life in Russia

Upon his return from a trip to Europe, Karamzin settled in Moscow and began his career as a professional writer and journalist, starting to publish the Moscow Journal of 1791-1792 (the first Russian literary magazine in which, among other works by Karamzin, the story “Poor Liza"), then released a number of collections and almanacs: "Aglaya", "Aonides", "Pantheon of Foreign Literature", "My Trifles", which made sentimentalism the main literary trend in Russia, and Karamzin - its recognized leader.

Emperor Alexander I by personal decree of October 31, 1803 bestowed the title of historiographer Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin; 2 thousand rubles were added to the title at the same time. annual salary. The title of a historiographer in Russia was not renewed after Karamzin's death.

From the beginning of the 19th century, Karamzin gradually moved away from fiction, and since 1804, being appointed by Alexander I to the position of a historiographer, he stopped all literary work, "taking the veil of historians." In 1811, he wrote a "Note on Ancient and New Russia in its Political and Civil Relations", which reflected the views of the conservative strata of society, dissatisfied with the emperor's liberal reforms. Karamzin's task was to prove that there was no need to carry out any transformations in the country.

"A note on ancient and new Russia in its political and civil relations" also played the role of outlines for the subsequent enormous work of Nikolai Mikhailovich on Russian history. In February 1818, Karamzin put on sale the first eight volumes of The History of the Russian State, three thousand copies of which were sold out within a month. In subsequent years, three more volumes of the History were published, and a number of its translations into the main European languages appeared. The coverage of the Russian historical process brought Karamzin closer to the court and the tsar, who settled him near him in Tsarskoye Selo. Karamzin's political views evolved gradually, and by the end of his life he was a staunch supporter of absolute monarchy.

The unfinished XII volume was published after his death.

Karamzin died on May 22 (June 3), 1826 in St. Petersburg. His death was the result of a cold he received on December 14, 1825. On this day, Karamzin was on Senate Square [source not specified 70 days]

He was buried at the Tikhvin cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

Karamzin - writer

“The influence of Karamzin on literature can be compared with the influence of Catherine on society: he made literature humane,” wrote A. I. Herzen.

Sentimentalism

The publication by Karamzin of Letters from a Russian Traveler (1791-1792) and the story Poor Lisa (1792; a separate edition in 1796) opened the era of sentimentalism in Russia.

Liza was surprised, dared to look at the young man, blushed even more and, looking down at the ground, told him that she would not take a ruble.

- For what?

- I don't need too much.

- I think that beautiful lilies of the valley, plucked by the hands of a beautiful girl, are worth a ruble. When you don't take it, here's five kopecks for you. I would always like to buy flowers from you; I would like you to tear them up just for me.

Sentimentalism declared feeling, not reason, to be the dominant of "human nature", which distinguished it from classicism. Sentimentalism believed that the ideal of human activity was not the "reasonable" reorganization of the world, but the release and improvement of "natural" feelings. His hero is more individualized, his inner world is enriched by the ability to empathize, sensitively respond to what is happening around.

The publication of these works was a great success with the readers of that time, "Poor Lisa" caused many imitations. Karamzin's sentimentalism had a great influence on the development of Russian literature: it was repelled [source not specified for 78 days], including Zhukovsky's romanticism, Pushkin's work.

Poetry Karamzin