Victory ship model deagostini waterline. Admiral Nelson's Victoria is a complete fake. Discipline and punishment

Armament

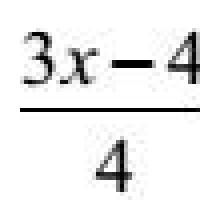

- 12-pound light guns - 44 pieces;

- 24-pound light guns - 28 pieces;

- 32-pound linear guns - 30 pcs.;

- 64-pound carronades - 2 pcs.

HMS Victory (1765) (Russian: "Victoria" or "Victory") - a battleship of the first rank of the Royal Navy of the British Navy. He took part in many naval battles, including the Battle of Trafalgar. Currently, the ship is turned into a museum, which is one of the main attractions of Portsmouth..

History of creation

On July 23, 1759, a ceremony was held at the Chatham shipyard to lay the keel of the new ship, which was a 45-meter long elm beam. The year 1759 was a year of military victories for England (at Minden and Hesse the French suffered particularly heavy defeats), so the newly built ship was given the name HMS Victory, i.e. “Victory”. By that time, four ships bearing this name had already served in the English Navy. Last HMS Victory was a 110-gun ship of rank I, built in 1737. In his seventh year of service, he was caught in a severe storm and died along with his entire crew.

Construction progressed slowly, because The Seven Years' War was going on and the shipyard was mainly busy repairing ships damaged in battles. In this regard, there was not enough strength or funds for a new ship. When the Seven Years' War ended, only the wooden frame of the future large ship stood in the dock.

But this leisurely construction played a positive role and was beneficial. A significant part of the timber material had been stored at the shipyard since 1746, and over the many years while construction was underway, the material acquired excellent strength qualities.

Only six years later, after laying the keel, on May 7, 1765 HMS Victory was launched. It was the largest and most beautiful ship that was ever built.

Prerequisites for creation

In 1756, the well-known Seven Years' War began in history, in which many European countries, including Russia, participated. The war was started by Great Britain, which could not share the colonies in North America and the East Indies with France. In this war, both countries needed a strong navy.

At that time, the British fleet had only one large, 100-gun battleship Royal James. The Admiralty ordered Chief Inspector Sir Thomas Slade to urgently build a new hundred-gun ship, using Royal James and making the necessary design improvements.

Description of design

The best types of wood were used in the construction of the building. The frames were made of English oak. The builders provided two hull skins: external and internal. The outer skin was made of Baltic oak, specially brought to England from Poland and East Prussia. In 1780, the underwater part of the hull was covered with copper sheets (3,923 sheets in total), which were attached to the wooden planking with iron nails.

The bow of the ship was decorated with a huge figure of King George III wearing a laurel wreath, supported by allegorical figures of Britain, Victory and others. At the aft end there were intricate carved balconies.

As was customary on ships of that time, no superstructures were provided on the deck. Near the mizzen mast there was a platform for the helmsman. There was a steering wheel for shifting the huge rudder located behind the stern. In order to cope with it, great efforts were needed, and usually two or even four of the strongest sailors were put at the helm.

At the stern was the best admiral's cabin, and below it was the commander's cabin. There were no cabins for the sailors; bunks were hung on one of the battery decks for the night. (As a rule, the bunks were pieces of thick canvas measuring 1.8 X 1.2 m, from the narrow sides of which there were thin but strong ropes, tied together and attached to a thicker one. Finally, the rope was tied to slats nailed to Early in the morning, the bunks were tied together using wooden beams and placed in special boxes located along the sides.

In the lower tween deck of the ship there were storerooms for provisions and crew chambers where barrels of gunpowder were stored. There was a bomb magazine in the bow of the tween deck. Of course, there were no mechanical means for lifting gunpowder and cannonballs, and during the battle all ammunition was lifted by hand, transferring from deck to deck by hand (this was not so difficult on ships of that time, since the distances between decks did not exceed 1.8 m ).

The big problem on any wooden ship is the inability to be completely watertight. Despite the most careful caulking and sealing of seams, water invariably seeped out, accumulated and began to emit a putrid odor, and contributed to decay. Therefore on HMS Victory, as on any other wooden ship, the sailors were forced to periodically go down inside the hull and pump out the bilge water, for which hand pumps were provided in the midship frame area.

Above deck HMS Victory three masts rose, which carried the full sailing rig of the ship. The sail area was 260 square meters. m. Speed up to 11 knots. According to the custom of that time, the sides of the hull were painted black, and yellow stripes were drawn in the area of the gun ports.

Crew and life

The cockpits traditionally housed the sailors, while the officers were provided with cabins. The lower deck was called the cockpit, where the crew settled down to sleep, first right on the deck, then in hanging bunks.

During the Battle of Trafalgar the crew consisted of 821 men. It would be possible to get by with far fewer men, but greater numbers are necessary to maneuver and fire the guns.

Most of the crew, more than 500 people, are experienced sailors who sailed and fought on ships. Their salaries were assessed according to their skill and experience.

Daily diet and food storage

It is important that food supplies remain in proper condition, because... the team is on the high seas. The diet on the ship was limited: salted beef and pork, cookies, peas and oatmeal, butter and cheese. Barrels and bags were used for storage. Food safety was carried out in the hold.

By the time of the Battle of Trafalgar, scurvy, caused by a lack of vitamin C in the diet, had begun to spread. To overcome this disease, fresh vegetables were regularly taken with the addition of lemon juice and a small amount of rum. In general, the diet was sufficient and amounted to approximately 5,000 calories per day, which was vital for keeping the crew healthy during heavy physical work.

The daily diet included 6.5 pints of beer; on a long hike this norm was replaced by 0.5 liters of wine or half a pint of rum. For work in the galley, 4-8 people were allocated under the direction of the ship's cook.

Discipline and punishment

Constant discipline was required to operate the ship efficiently and safely, as well as to achieve successful victory.

Crew discipline was organized in several ways. Work for 1-2 hours was carried out under supervision. For more complex activities on board the ship, each person was given a specific place to work. Control was carried out by officers.

When committing a crime or misdemeanor, the captain announced penalties to the guilty party. Most often, the punishment was lashes from 12 to 36 strokes for crimes: drunkenness, insolence or neglect of one's duties. This type of punishment was carried out mainly by the boatswain, after tying the offender to a wooden grate on the deck and stripping him to the waist. A sailor caught stealing must run through a line of crew members who beat him with a knotted rope at the ends.

Another method of punishment was correction by starvation. The offender was shackled in leg shackles on the battery deck and fed only bread and water.

The most severe punishments for crimes such as mutiny or desertion were flogging and hanging. The perpetrators could receive up to 300 lashes, which were often fatal.

Armament. Modernization and refurbishment

Each gun was mounted on a carriage, with the help of which it was rolled back to load the cannonball. In one gun crew there were 7 people who were responsible for the cannon being loaded in a timely manner and the shot fired strictly on command. A charge of gunpowder was placed in the barrel of the gun, followed by a wad, then a cannonball and another wad. The charge with gunpowder was pierced so that it could easily ignite from a spark, after which more gunpowder was added. The gun commander moved the bolt to the side and pulled the cord, after which a spark appeared, thanks to which the cannonball rushed to the intended target. The sailors loaded the cannons with different shells, which were intended for different types of destruction. There was enough gunpowder on the ship to blow up the entire ship. Powder warehouses were illuminated by lanterns standing behind the glass window of the adjacent room, and coal panels in the walls protected the cellar from moisture.

The composition of the artillery armament changed several times during its many years of service.

The original project called for the installation of one hundred guns.

By the beginning of the 1778 campaign, Admiral Keppel ordered the replacement of 30 units. 42-pounder guns on the gondeck to lighter 32-pounder ones.

However, already in 1779 the composition of the weapons became the same.

In July 1779, the Admiralty approved a standard provision for supplying all ships of the fleet with carronades, according to which in 1780 six 18-pound carronades were additionally installed on the poop, and two 24-pound ones on the forecastle, which were replaced by 32-pounders in 1782. At the same time, twelve 6-pounder guns were replaced by ten 12-pounder and two 32-pounder carronades, bringing the total number of carronades to ten. The total number as of 1782 was 108 guns.

In the first half of the 1790s, the ships of the British fleet began to be re-equipped with new cannons designed by Thomas Blomefield with a finned ear and new carronades. In 1803 HMS Victory underwent a major overhaul, after which its artillery armament increased: in the quarterdeck by 2, on the forecastle it was replaced by 2 carronades of 24-lb. There were 102 guns in total.

By the time of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, two 12-pounder medium guns were installed on the forecastle, and the 24-pounder carronades were replaced with 64-pounder ones, bringing the total number to 104 guns.

Service history

Service

The ship was launched at Chatham two years after the end of the Seven Years' War, on 7 May 1765, but active service did not begin until 1778, when the Admiralty decided to arm the ship and prepare her for active service. The commissioning of the ship was a consequence of the events unfolding at that time. In March 1778, the French king Louis XVI declared the recognition of the North American states as independent from England and announced his intention to establish trade and economic relations with free America. If necessary, France was ready to defend this trade by force. In response, George III recalled his ambassador from Paris. The smell of war was in the air and the Admiralty began to gather forces.

Augustus Keppel was appointed commander of the fleet, who elected HMS Victory his flagship ship. The first commander was John Lindsay.

It took approximately two and a half months to prepare and armament, after which King George III visited Chatham. After the visit of the king, who was satisfied with the work of his shipyard, HMS Victory transferred to Portsmouth. While stationed at the Spithead roadstead, Augustus Keppel ordered that the thirty 42-pounder guns on the gondeck be replaced with lighter 32-pounder ones, which reduced the weight load and slightly increased the free space on the deck.

Battle of Ouessant Island

The Battle of Ushant Island (English: Battle of Ushant, French: Bataille d'Ouessant) - a naval battle between the English fleet under the command of Admiral Augustus Keppel and the French fleet under the command of Count Gillouet d'Orvilliers, which took place on July 27, 1778 near the island of Ouessant during American Revolutionary War The result of the battle caused discord in the Royal Navy and throughout British society.

On the morning of July 27, 1778, with a wind from the SW, the fleets were 6-10 miles apart. Both were sailing on port tack to the NW. Both were in some confusion, but the French held the column and the British formed a bearing to the left. Thus, the latter could, after tacking, immediately form a line of battle steeply to the wind. Judging that it was unprofitable to build a line methodically, Keppel raised the “general pursuit” signal, again trying to get closer. His ships, each independently, made a turn towards the enemy, after which Hugh Palliser's division (eng. Hugh Palliser, flagship HMS Formidable) became the right wing, farthest from the enemy; Keppel with HMS Victory was in the center, and Harland (eng. sir Robert Harland, flagship HMS Queen) on the left flank. At 5:30 a.m., the seven best walkers in Palliser's division were signaled to pursue the enemy downwind.

At 9 am, the French admiral ordered his fleet to jibe successively, which brought him somewhat closer to the British and temporarily doubled the line. But the advantage of the position was to remain. However, the wind setting by two points, from SW to SSW, slowed down the maneuver and increased the drift of the French. Their order became even more disordered. The lead ships, which had already made a turn, were prevented from arriving by their own end ships, which were heading in the opposite direction. Only after passing the last ship in the line could they take a steeper turn to keep the British at bay.

When, at about 11:00 a.m., Orvillers was already making a new turn on the opposite course. Realizing that the wind allowed Keppel to catch up with the end ships and start a battle at will, he decided to act actively, since he could no longer avoid the battle.

Keppel did not raise the signal to build a line, correctly assessing that the immediate task was to force the evading enemy into battle. In addition, 7 rearguard ships moved to the wind after the morning signal, and now almost his entire fleet could enter the battle, albeit in some disorder. The start of the battle was so sudden that the ships did not even have time to raise their battle flags. According to the testimony of British captains, the formation was so uneven that Palliser's flagship, Formidable, almost all the time he put the cruising topsail into the wind so as not to run into the one in front Egmont. Wherein Ocean, which barely had enough space to shoot into the interval between them, stayed to the left and out of the wind, but even then risked falling on Egmont, or get hit by one of them.

Passing on a counter course along the enemy's formation, under reefed sails, both fleets tried to inflict as much damage as possible. As usually happens on such courses, the shooting took place in a disorganized manner, with each ship choosing the moment to fire the salvo. The British shot mainly at the hull, the French tried to hit the rigging and spars. The British were sharply close-hauled, the French were four points freer. Their leading ships could have been brought down and closed the distance, but fulfilling their duty, they supported the others. In general, according to d'Orvillier's order, they built a steeper line, which gradually took them further from the British guns. It was an unprepared skirmish at a long distance, but still better than nothing. Against the usual, the British rearguard suffered the most - his the losses were almost equal to those of the other two divisions - mostly he was closer to the enemy.

As soon as the 10 ships of the vanguard separated from the French, Harland, anticipating the admiral's signal, ordered them to turn and follow the enemy. Around 1 o'clock in the afternoon when HMS Victory left the shelling zone, the center also received the same signal - Keppel ordered a jibe: the cut rigging did not allow it to turn into the wind. But that is why the maneuver required caution. Only by 2 o'clock HMS Victory laid down on a new tack, following the French. The rest turned as best they could. Formidable Palliser at this time was passing towards the flagship from the wind. Four or five ships, uncontrollable due to damage to the rigging, remained to the right and to leeward. Around that time the signal “engage in battle” was lowered and the signal “form the battle line” was raised.

In turn, d'Orvilliers, seeing the disarray into which the British had arrived after all the maneuvers, decided to take advantage of the moment. His fleet was moving in a fairly orderly column, and at 1 o'clock in the afternoon he ordered a turn sequentially, with the intention of passing the British out of the wind. At the same time, the French they could bring into battle all the guns on the windward side, that is, on the other side, the lower ports had to be kept closed, but the lead ship did not see the signal, and only de Chartres, the fourth from the beginning, rehearsed and began to turn, passing by the flagship. clarified his intention, but due to an error by the lead ship, the opportune moment was missed.

Only at 2:30 the maneuver became obvious to the British. Keppel with HMS Victory immediately jibed again and began to descend downwind towards the uncontrollable ships, still holding the signal to form a line. He probably intended to save them from impending destruction. Harland and his division turned immediately and aimed under the stern. By 4 o'clock he had lined up. Palliser's ships, repairing damage, occupied places in front and behind Formidable. Their captains later stated that they considered the ship of the vice admiral, not the commander-in-chief, to be the equalizer. Thus, from the windward, 1-2 miles astern of the flagship, a second line of five ships formed. At 5 o'clock Keppel and the frigate sent them an order to join quickly. But the French, having already completed their maneuver, did not attack, although they could have.

Harland and his division were ordered to take a place in the vanguard, which he did. Palliser did not approach. By 7:00 pm Keppel finally began raising individual signals to his ships, ordering them to abandon Formidable and join the line. Everyone obeyed, but by this time it was almost dark. Keppel considered it too late to resume the battle. The next morning, only 3 French ships remained in sight of the British. The French avoided further battle.

Battle of Cape Spartel

The Battle of Cape Spartel was a battle between the British fleet of Lord Howe and the combined Spanish-French fleet of Luis de Cordoba, which took place on October 20, 1782 on the approaches to Gibraltar, during the American War of Independence. At dawn on October 20, the two fleets crossed paths 18 miles off Cape Spartel on the Barbary coast. This time Howe was to leeward and almost stopped his fleet. Thus, he gave the Spaniards the choice to engage or evade at will.

Cordoba ordered a general pursuit, regardless of the observance of formation. For the Spaniards, among whom there were especially slow ones, for example the flagship Santisima Trinidad, it was the only way to get closer. By about one o'clock in the afternoon the distance between the fleets had been reduced to 2 miles - twice the maximum firing range. The Franco-Spanish ships were to windward and to the right. Santisima Trinidad by this time he had reached the center of the line, which the Spaniards had to build again.

During this time, Howe closed the line, concentrating his 34 ships against the enemy's 31. The standard counter-move in such cases is to grab the short line from the ends. But the advantage of the British movement did not allow the enemy such a maneuver. Instead, some of his ships, including two three-deck ones, were actually out of the battle.

At 5:45 p.m. the leading Spaniards opened fire. An exchange of salvos followed, with both fleets continuing to move; the British gradually pulled forward without engaging in close combat. The shooting stopped as night fell. The loss of life was approximately equal on both sides.

On the morning of October 21, the fleet was separated by approximately 12 miles. Cordova repaired the damage and was ready to continue the fight, but this did not happen. Taking advantage of the gap, Howe took the fleet to England. On 14 November he returned to Spithead.

HMS Victory was in the 1st Central Division under the command of Captain John Livingstone, being the flagship of Admiral Lord Richard Howe.

The battle did not bring a decisive victory to anyone. But the British completed the important operation without losing a single ship. The fleet averted the threat of a new assault on Gibraltar. In essence, the siege was lifted. All this lifted the spirit of the British after recent losses (the scale of the victory at All Saints was not yet fully known) and improved the position of their diplomacy in the peace negotiations that soon began.

Battle of Cape San Vicente

Having entered naval service at the age of 12, Horatio Nelson had already reached the rank of lieutenant by the age of 18, and at 26 he became captain of a warship, on board of which he took part in the battle on February 14, 1797 at Cape Sao Vicente in Portugal, which occurred between the English a fleet under the command of Admiral John Jervis and a Spanish squadron. Having reached Cape San Vicente, the English fleet of 15 ships found itself within sight of the Spanish fleet of 26-27 ships, 8 of which were at a distance insufficient for a quick approach to the rest of the forces. In addition, the wind rose at sea, which also contributed to the natural division of the Spanish fleet, whose commander was José de Cordova.

Realizing how important it was for the English fleet to win this particular battle, John Jervis decided at dawn on February 14 to attack most of the Spanish ships, in the hope that the rest would not have time to get close enough to fire. The English warships lined up and prepared for the attack, the Spaniards, who had not noticed the fleet for a long time due to heavy fog, were not ready for it, this is what the experienced admiral actually hoped to play, deciding to go through the ranks of enemy ships. It was planned that the ships of the English fleet, having come into contact with the Spanish ships, would tack and thus encircle most of the enemy. But the maneuver was unsuccessful, since one of the ships lost the foresail and top yards during a turn, and, accordingly, was forced to gybe, which gave the Spaniards some advantage.

Seeing that the English ships could lose all the advantage they had gained, and the initiative would pass to the Spaniards, Captain Nelson made the fateful decision to violate the admiral's orders and turn the ship, engaging in battle with one of the enemy's most well-equipped warships. Recognizing his maneuver, Admiral Jervis ordered the remaining ships nearby to assist Nelson, an order that became decisive in the subsequent defeat of the Spanish flotilla.

Nelson's prank disrupted the even linear formation of the ships, but saved the fleet from inevitable defeat, therefore, instead of the gallows, which threatened the captain for violating the order of a superior, he was, under the patronage of Jervis, promoted to the rank of rear admiral, received a lifelong charter of nobility, became a baron and was honored with the Order of the Bath.

The crew of the ship Captain, whose captain was Nelson, thanks to his maneuver captured two Spanish ships and also did not go without rewards, in fact, like the admiral himself, who became a lord. Unfortunately, most of the brave captain's crew was wounded or killed, since the ship was in the very center of a firefight between the British and the Spaniards.

Participation in the Battle of Trafalgar

Historical events in Europe at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries were mainly influenced by Napoleon Bonaparte. The French had the upper hand already in 1803, but the Emperor's thoughts extended across the English Channel to the British Isles. Napoleon had no doubt that someday he would have the opportunity to defeat his sworn enemy. He also realized that the conquest of Great Britain was impossible without the conquest of the British fleet. His attempt to achieve his intended goal resulted in a bloody naval battle near the Spanish city of Cadiz. This naval battle became one of the most famous in the world naval history, and today it is called the Trafalgar naval battle.

On October 21, 1805, Villeneuve led his ship crews to a naval battle near Cape Trafalgar. A few months before the battle, back in Toulon, the French admiral outlined the plan of the conservative British to the ship commanders. The British would not be content with a single line of ships parallel to the French formation; they would place two columns at right angles to them and try to break through the French naval formation in several places, in order to then finish off the scattered forces. In addition, 33 French ships, against 27 English ships, was considered a certain advantage. However, the guns of Admiral Villeneuve's ships were not entirely accurate and did little damage, and the reload time was excessively long.

The British plan was deliberately simple. They divided the fleet into two squadrons. One was commanded by Admiral Horatio Nelson, who intended to break the enemy's chain and destroy the ships in the vanguard and in the center, and the second squadron, under the command of Rear Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, was to attack the enemy from the rear.

At 06:00 on 21 October 1805, the British fleet formed into two lines. The flagship of the first line, consisting of 15 ships, was the battleship Royal Sovereign, carried by Rear Admiral Collingwood. The second line, under the command of Admiral Nelson, consisted of 12 ships, and the flagship was the battleship HMS Victory. The wooden decks were sprinkled with sand, which protected against fire and absorbed blood. Having removed everything unnecessary that could interfere, the sailors prepared for battle.

At 08:00, Admiral Villeneuve gave the order to change course and return to Cadiz. Such a maneuver before the start of a naval battle upset the battle formation. The French-Spanish fleet, which was a crescent-shaped formation curved to the right towards the mainland, began to turn around chaotically. Dangerous gaps in the distance appeared in the formation of ships, and some ships, in order to avoid colliding with their neighbors, were forced to “fall out” of formation. Admiral Nelson, meanwhile, was approaching. He intended to break the line before the French sailing ships approached Cadiz. And he succeeded. A great naval battle began. Cannonballs flew, masts began to break and fall, people were dying, the wounded were screaming. It was complete hell.

In a number of battles in which the British were victorious, the French took a defensive position. They sought to limit the damage and increase the chances of retreat. This French position resulted in flawed military tactics. For example, gun crews were ordered to aim at masts and rigging to deny the enemy the opportunity to pursue French ships if they retreated. The British always aimed at the hull of a ship to kill or maim the enemy crew. In the tactics of naval combat, longitudinal shelling of enemy ships was considered the most effective, with the shelling being conducted at the stern. In this case, with an accurate hit, the cannonballs rushed from stern to bow, causing incredible damage to the ship along its entire length. During the Battle of Trafalgar, the French flagship was damaged by such shelling. Bucentaure, who lowered the flag, and Villeneuve surrendered. During the battle, it was not always possible to perform the complex maneuver necessary for a longitudinal attack on the ship. Sometimes the ships stood alongside each other and opened fire from a short distance. If the ship's crew survived the terrible shelling, then hand-to-hand combat awaited them. Opponents often sought to capture each other's ships.

Nelson chose to strike the most vulnerable ship Redoutable. Having come close, the boarding battle began. The sailors mowed each other down for 15 minutes. Shooter on Mars Redoutable spotted Nelson on the deck and shot him with a musket. The bullet went through the epaulette, pierced the shoulder and lodged in the spine. The admiral gave the command to cover his face so as not to demoralize the sailors.

Admiral Villeneuve gave the flag signal to all ships to attack, but there was no reinforcement. Nelson carried out his plan and plunged the French into complete chaos. The naval battle line was broken. The French ships lost contact with the Spaniards. The balance of forces changed not in favor of the French, defeat was inevitable. The heavy English artillery fired non-stop, the cannonballs fell into a pile of corpses that were not thrown into the sea in time. The surgeons were completely exhausted; it took only 15 seconds to amputate the limbs, otherwise the wounded man simply could not stand the pain.

At 17:30 the naval battle ended. By this point, 18 French and Spanish sailing ships could not continue the battle and were captured.

The Battle of Trafalgar is considered the largest naval battle in the history of the British Navy. The British lost 448 sailors, including the commander of the English fleet, Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, and 1,200 wounded. The combined Franco-Spanish fleet lost 4,400 people killed and 2,500 wounded. More than 5 thousand were captured, hundreds of survivors went deaf, and many ships were broken beyond repair.

The result of the Battle of Trafalgar affected the fate of both the winner and the loser. France and Spain lost their naval power forever. Napoleon abandoned his plans to land troops in England and invade the Kingdom of Neopolitan. Great Britain finally acquired the status of mistress of the seas.

Ships of the same name

A total of six ships of the British Royal Navy were built, which were called HMS Victory:

HMS Victory (1569)- 42-gun ship. At first it was called Great Christopher. Purchased by the English Royal Navy in 1569. Dismantled in 1608.

HMS Victory (1620)- 42-gun “big ship”. Launched at the Royal Dockyard at Deptford in 1620. Rebuilt as an 82-gun 2nd rank in 1666. Dismantled in 1691.

HMS Victory- 100-gun ship of rank 1. Launched in 1675 as Royal James, renamed 7 March 1691. Rebuilt in 1694-1695. Burnt down in February 1721.

HMS Victory (1737)- 100-gun ship of rank 1. Launched in 1737. Wrecked in 1744. Found in 2008.

HMS Victory (1764)- 8-gun schooner. Served in Canada, burned in 1768.

HMS Victory (1765)- 104-gun ship of 1st rank. Launched in 1765. Admiral Nelson's flagship during the Battle of Trafalgar.

This ship in art

In memory of the victory at Trafalgar and the remarkable naval commander, Trafalgar Square was created in the center of London, on which a monument to Nelson was erected. During the Battle of Trafalgar, a cannonball knocked down the mizzen mast, two other masts were knocked out of their steps, and most of the yards were damaged. The ship was sent for repairs, during which the most serious damage was eliminated.

|

|

||

After renovation HMS Victory took part in several operations in the Baltic and ended his military career as a transport in 1811. On December 18, 1812, the ship was excluded from the lists of the British Navy, and, according to the Admiralty inspector, HMS Victory was in “dry and good condition,” and the ship was already 53 years old! Soon after its decommissioning, the British began to treat it as a monument ship, and no one dared to destroy it.

In 1815, the ship was put in for major repairs. The hull and other equipment were carefully inspected, repairs were carried out, the figurehead was again replaced, and the hull was repainted again (wide white stripes were drawn in the area of the gun ports). After repairs, the ship remained in the port of Gosport, near Portsmouth, for a hundred years. From 1824 to HMS Victory a gala dinner was held annually in memory of the Battle of Trafalgar and Admiral Nelson, and in 1847 HMS Victory was declared the permanent flagship of the commander of the Home Fleet of England, that is, the fleet directly responsible for the inviolability of British territory. However, the veteran ship was not looked after as well as it should have been. The hull gradually collapsed, its bend in the bow reached almost 500 mm, and by the beginning of the 20th century the hull was in very poor condition.

There were rumors that the ship needed to be sunk, and, most likely, this would have happened if Admiral D. Sturdy and Professor J. Callender, the author of a number of famous books about Admiral Nelson and his remarkable ship, had not come to the defense of the famous ship. Thanks to their active intervention, fundraising began in England under the motto “Save HMS Victory". It is characteristic that the Admiralty limited itself to providing a dry dock for restoration work, which was carried out in 1922. Interestingly, the restorers considered it possible not to replace half of the logs and boards from which the ship was once built, but to limit themselves to impregnating them with a special solution, protecting the tree from destruction.

During the Second World War, when German planes made frequent raids on England, a 250-kilogram bomb fell between the wall of the dock and the side of the ship. A hole with a diameter of 4.5 m appeared in the hull. Specialists responsible for the preservation of the historical ship discovered that with the appearance of this hole, the ventilation of the interior spaces has noticeably improved.

After the Second World War, the ship was renovated. To ensure water resistance, about 25 km of joints were caulked, the spars and rigging were updated, and the hull was repaired using English oak and Burmese teak. To reduce the load on the old hull, the guns were removed from the ship, and now all the ship's guns stand on the shore, surrounding the dry dock in which it stands HMS Victory.

The struggle for the life of the monument ship does not stop. Its worst enemies are wood-boring beetles and dry rot. This is one of the most common weaknesses in using wood. Suddenly, another danger was discovered: the guys, with the help of which the masts, stays and shrouds are secured, become tense in rainy weather, and sag in dry weather, which could eventually lead to the destruction of the masts. In 1963, it was necessary to spend 10 thousand pounds sterling to replace the guy wires with cables made of Italian hemp.

HMS Victory has been permanently moored in the oldest naval dock in Portsmouth since January 12, 1922, it is one of the most popular museums in England. On some days, the ship is visited by up to 2 thousand people, and every year 300-400 thousand people come here. All proceeds from visitors to this unusual museum go towards maintaining the ship.

see also

Literature and sources of information

1. Grebenshchikova G. A. Battleships of the 1st rank “Victory” 1765, “Royal Sovereign” 1786. - St. Petersburg: “Ostrov”, 2010. - 176 p. - 300 copies.

2. John McKay The 100-gun ship Victory. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 2002.

Links

1. Museum ship HMS Victory HMS Victory

The publisher reserves the right to change the characteristics (material, color, size, quantity, completeness, packaging, etc.) of the supplied ship model parts. The included parts may differ from those shown in the illustrations in the magazine.

1. What are the dimensions of the ship model upon completion of installation?

The flagship model has a length of 125 cm and a height of 85 cm.

2. How many issues are there in the “Admiral Nelson's Ship Victory” collection?

The collection is planned to have 120 weekly issues.

3. What is the price of the collection releases?

4. What are the ship parts made of?

Like real ships, the hull of the model is made of specially selected wood. The cladding is made of wooden planks, and the strength of the structure is ensured by the use of metal fasteners. The figures of the ship's crew members are made of metal. You can color them by hand!

5. What should I do if I still have questions about assembling the model after reading the assembly instructions in the magazine and watching the video disc?

In this case, you can ask a question on our hotlines 8-800-200-02-01 (for regions), 8 495 660 02 02 (for Moscow). If your question turns out to be complex, we will connect you with a modeling specialist. It is open on Tuesdays from 10 am to 1 pm and on Fridays from 4 pm to 7 pm. You can also get information at.

6. How reliable is the model compared to the original?

The model's fidelity to the drawings recreating the ship is very high. For its production, archival documents and specialized literature were used. In addition to the high reliability of the ship's appearance, our model, if desired, allows you to assemble the ship in such a way that you can see the internal structure of the flagship.

7. What should I do if I missed or didn’t have time to buy the next issue of the collection?

You can order missed numbers on the website – Order numbers or by calling the hotline:

8 800 200 02 01

for regions of Russia

8 495 660 02 02

for Moscow

8. In which CIS countries is the collection “Admiral Nelson’s Ship “Victory”” sold?

Currently the collection is only available in Russia. Sales in other countries will be announced separately.

9. What is on the video disc that comes with issue 1 of the collection?

The video included with the first release of the series is intended to explain the stages of the assembly processes of the flagship model. Also on it you can view the finished model in all details!

10. Will there be a special folder in the collection for storing magazines?

11. Are special tools and materials required for installation?

Tools described on the assembly instructions pages may be used for assembly. We recommend purchasing a special set of tools “Admiral Nelson’s ship “Victory”” (recommended retail price: 499 rubles*). The date of its availability for sale will be announced later.

The set of tools that will go on sale includes:

- Brush

- Model knife

- Wire cutters

- Skin holder

- Hammer

- Mini drill

- Replacement chuck for drill

- Tweezers

- Drill

- Nailer

- One file

12. What other additions to the collection can I purchase separately?

To make it easier to assemble the model, a special magnifying glass for modeling will be available for sale (recommended retail price: 295 rubles*), a set of tools (recommended retail price: 499 rubles*), a folder for storing magazines (recommended retail price: 149 rubles*), and a demonstration stand ( will be released towards the end of the collection).

13. I bought the first set. Where should you start?

Any work begins with organizing the workplace. First, you need to select several boxes of various sizes in which you will store the kit parts until they are installed on the model, and assemble a temporary slipway on which the ship will be assembled. A temporary slipway (working base) will be included with one of the releases of the collection.

14. What will the ship be placed on during its construction?

During the construction period, the ship model will be placed on a working stand. It will be included with one of the collection's releases.

15. Are special precautions required when storing a sailboat?

Of course, you need to protect it from bumps or falls. To protect against dust, it is recommended to make a cap from polished organic glass or place the model in a glass display case or some kind of case that will preserve the beauty of the model for a long time.

HMS Victory (1765) is a 104-gun ship of the line of the first rank of the Royal Navy of Great Britain. Laid down on July 23, 1759, launched on May 7, 1765. He took part in many naval battles, including the Battle of Trafalgar, during which Admiral Nelson was mortally wounded on board. After 1812, she did not take part in hostilities, and since January 12, 1922, she has been permanently moored in the oldest naval dock in Portsmouth. Currently, the ship has been restored to the condition in which it was during the Battle of Trafalgar and turned into a museum, which is one of the main attractions of Portsmouth.Quite a long time ago, as a child, I collected Ognykov’s “Comrade” and “Eagle”. Assembled completely from the box, without painting. Then there was “Pourquois Pa”, I also assembled the version out of the box, but with coloring. And so, this fall I remembered my once forgotten hobby and decided to collect something. I chose the battleship HMS Victory from Zvezda. Although later, when I started assembling, I realized that the model was quite complicated for the first work after so many years, especially in terms of painting. But still he completed the work.

The ship took about 5 months to build. I painted it entirely with brushes, acrylic “Star” and a little “Tamiya”. Later I discovered that the “Star” paint adheres rather poorly to the surface and can be easily scratched with a fingernail. Because of this, the entire model was first covered with glossy and then matte Tamiya varnish from cans. The quality of the parts is quite mediocre, there is enough flash, a lot had to be “finished with a file”. I did not use primer or putty on this model.

I assembled it according to the instructions, there were minimal changes, except that I added a fence near the ladder from the lower deck. I did not use the paint scheme proposed by the star; I relied on photographs of the prototype taken in the summer of 2005. I didn’t like the plastic sails that came with the kit, so I didn’t install them at all. The rigging in the instructions is quite thin, so I decided to use the Mamoli drawings. The rigging was carried out as completely as the scale and my hands allow))). I did not use blocks. The details of the spar are quite thin, then I noticed that the topmast on the mizzen mast was pulled a little to the side (maybe I’m wrong in the name).

There are enough stocks. For example, the paint lines are not always straight, because... I used masking tape, it doesn’t fit well everywhere, and in these places the paint flows under it, I tried to fix it with a toothpick. Also, the painting of small parts was not quite even, for example on the aft gallery, although I painted it with a toothpick, it still didn’t turn out very smooth - I lack experience))). Also quite a large jamb, I don’t know whether it’s just parts in the kit, or I assembled it crookedly: I started trying on the back wall of the aft gallery, it turned out to be a little wider in width. I couldn't think of anything else to do except grind down the right side a little.

Scale: 1/180

In the end, the result is in front of you. Ready to catch stools)))

In Portmouth there is a fake ship, not the Nelson ship itself, made in 1916 for the Museum.

“From January 12, 1922 to the present, in the city of Portsmouth, in the Maritime Historical Museum, there is an exact copy of the famous battleship, which personifies the centuries-old glory and victory of Britain in the Battle of Trafalgar, in which Russian sailors also took part.

http://korabley.net/news/samoe_izvestnoe_parusnoe_sudno_britanii_klassicheskij_linkor_victory/2009-10-23-395

And here is a repost of the photo report, from which it is clearly visible that this is a completely new ship.

Original taken from book_bukv

in the History of “Victoria” there will be!

In the process of clarifying some information about the history of the ship, it became clear.

That the longevity of the Victoria is still an exceptional case even by the standards of the English fleet.

That the history of the ship is not very simple and not as straightforward as they tell tourists.

That she is even more interesting than she previously thought.

And that finding it on the Internet, without inventions and inventions, is very difficult.

Therefore, here is a brief history of “Victoria” as presented by me.

Sources will be mentioned separately.

Part one. Design and construction

The ship's history began in February 1756, when surveyor engineer Thomas Slade,

was appointed Chief Builder of a new first-class battleship.

According to the terms of reference of the Admiralty, the Royal George was to serve as a prototype -

the only one-hundred-gun battleship in the British fleet at that time.

Slade was supposed to start building the ship by logging, which took several years

had to dry and ripen for work. But the Admiralty was in a hurry - the Seven Years' War began,

ships were needed. Then the builder found a warehouse of ten-year-old ship's wood

and there was no need to make compromises. There are opinions that due to the construction of the ship from a very old

and seasoned material he lived for such a long time.

In 1757, the Admiralty was again headed by Lord George Anson - a very energetic but efficient leader

and the storming at the shipyards stopped. Also, while Slade was looking for wood and producing blueprints,

England severely crushed France at sea. Apparently this is why Victoria was built slowly

and this is the second reason for her longevity.

July 23, 1759, on one of the slipways of Chatham - the main naval arsenal and shipyard of England -

The groundbreaking ceremony took place. Since the year was very fruitful for victories, the ship was given the name “Victory”,

despite the fact that it was already the fifth “Victory” of the British Navy, and despite the fact that

that the fourth "Victory" - a 110-gun ship of the first rank built in 1737, was lost during a storm

in 1744, as usual with the entire crew.

During those harsh war years, the shipyards of England were mainly engaged in the repair of ships,

damaged in battles and campaigns, and construction proceeded slowly. Therefore, in the spring of 1763,

when the Seven Years' War ended with the victory of England, "Victory" was

keel with frame ribs barely connected to each other.

But after the war, work began to boil - already on May 7, 1765, the ship was launched,

and although its completion took another 13 years, in 1778 the battleship Victory was added to the fleet lists.

The ship cost £63,176 to build - practically nothing

the country received another wonderful instrument of its history and glory.

Now Victory is painted according to the canons of the 18th century: black top, yellow middle like a beeline >

the figurehead after perestroika in 1799 became a heraldic wick >

Now all the rigging is made from Italian hemp, but once it was from Russian >

balconies and stern decor are also after the reconstruction of 1799

unoriginal

practically a fake >

Well, modern designers also chose the font, hello

in Nelson's time they used normal English typefaces

Caslon or Baskerville

so that the British would then sign their ship with a capital square

it's not even funny you know >

The ship I want to tell you about - HMS Victory, 1765, is the oldest operational ship in the world and is also the flagship of the Second Lord of the Admiralty/Commander-in-Chief of the Nation's Navy. She was designed by Thomas Slade, entered into the Navy as a combat unit in 1778, and remained in active service until 1812.

So, as Wikipedia says, - HMS Victory- 104-gun battleship of the first rank of the Royal Navy of Great Britain. Laid down on July 23, 1759, launched on May 7, 1765. He took part in many naval battles, including the Battle of Trafalgar, during which Admiral Nelson was mortally wounded on board. After 1812, she did not take part in hostilities, and since January 12, 1922, she has been permanently moored in the oldest naval dock in Portsmouth. Currently, the ship has been restored to the condition in which it was during the Battle of Trafalgar and turned into a museum, which is one of the main attractions of Portsmouth.

The ship is really beautiful! Especially outside! But due to heavy rain and wind, it was not possible to photograph it in all its glory. In addition, the ship is currently undergoing restoration - three masts, a bowsprit and rigging have been removed. As stated on the ship's official website, this is a unique opportunity to see how this legendary 18th century sailing ship was built and put into combat readiness. The last time the ship was in this condition was in 1944, so this is truly a unique opportunity (once in a lifetime, according to the website) to see Victory in such extreme maintenance conditions.

Once upon a time, at the beginning of the 19th century, the ship was decommissioned from the active fleet, stripped of its masts and turned into a floating warehouse; however, at the beginning of our century, the ship was restored to its original form and is still in service to this day with a commander and crew, consisting, however, not of sailors and gunners, but of guides. On the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar, Nelson's cry will rise from its mast: "England expects every man to do his duty."

Please note - on both sides of the upper deck there is an anti-fragmentation net, where the sailors' hammocks were stored; in battle, it served to protect against cannonballs and fragments. If a sailor fell overboard, a hammock was thrown to him so that he could stay on the water. The ship is equipped with four masts: a bowsprit, a foremast, a mainmast and a mizzen mast. The ship could raise 37 sails, which allowed it to reach speeds of up to 11 knots (20 km/h).

There were 102 guns of 32, 24 and 12 pounds caliber placed on three decks.

The best types of wood were used in the construction of the building. The frames were made of English oak. The builders provided two hull skins: external and internal. The outer skin was made of Baltic oak, specially brought to England from Poland and East Prussia. Subsequently, in 1780, the underwater part of the hull was covered with copper sheets (3923 sheets in total), which were attached to the wooden lining with iron nails.

Main cabin.

The admiral lived in this room. It is divided into two compartments - the dining room and the captain's salon.

In the dining room he relaxed with his officers and held meetings;

The captain's salon served as his office; Nelson's original round table has been preserved here.

During hostilities, this entire area of the ship became part of the upper cannon deck. The guns were placed in gun loopholes along the sides and, if necessary, at the stern.

The uniform is a replica of the uniform Nelson wore during the Battle of Trafalgar; The admiral's height was about 168 cm (according to other sources - 165, but his wax figure looks very small). The second uniform is the ceremonial one. Next you could go through the bedroom, where there is a copy of Nelson's bunk. Most senior officers had similar draped bunks. If an officer died at sea, the bunk became his coffin. The ship itself was very dark and cramped, with low ceilings and narrow passages. So, not everything we wanted was captured.

Lower cannon deck.

The original oak deck flooring has been preserved from the time the ship was built. This deck served as the main living quarters for sailors. At night, 480 people slept in hammocks suspended from beams. The next morning, the hammocks were rolled up, lifted to the upper deck and placed in a fragmentation net.

Lunches took place in even more cramped conditions. Approximately 560 crew members, divided into groups of 4-8 people, sat at 90 tables located on the deck. Breakfast consisted of thick oatmeal called bergoo and a hot drink made from burnt biscuit crumbs and hot water known as Scotch coffee. For lunch they served stewed corned beef, pork, or, less often, fish with oats or dried peas. Dinner consisted of biscuits with butter or cheese. To maintain strength and fight scurvy, the sailors were given lime juice, and whenever possible, fresh meat and vegetables were added to the diet. However, during long sea voyages, the quality of food deteriorated: biscuits infested with weevils, cheese often became moldy, and butter became rancid over time. Drinking water also spoiled, so sailors were allowed 4.5 liters of beer or 1 liter of wine or a quarter liter of rum or brandy per day. Despite the excessive supply of alcohol, drunkenness was considered a serious offense. The sailors were also given 1 kilogram of tobacco per month, which they usually chewed, and the caustic tobacco juice was spat into spittoons.

In the lower tween deck of the ship there were storerooms for provisions and crew chambers where barrels of gunpowder were stored. There was a bomb magazine in the bow of the tween deck. Of course, there were no mechanical means for lifting gunpowder and cannonballs, and during the battle all ammunition was lifted by hand, transferring from deck to deck by hand (this was not so difficult on ships of that time, since the distances between decks did not exceed 1.8 m ).

In the bow there is a ship's infirmary, separated from the rest of the deck by a canvas bulkhead on a wooden frame. Before the battle, the bulkhead was easily removed to free up space on the cannon deck, and the infirmary was moved to the lower deck (orlop deck).

Surgical department and surgical instruments….

After Lord Nelson was wounded by gunfire from an enemy ship, he was transferred here, where he was treated by the ship's surgeon, Dr. Beatty. Nelson died from his wounds at approximately 4:30 p.m. Before his death, he wished to be buried in England (usually sailors are buried at sea, and each officer on the ship slept in his own coffin to save space). His clothes were removed, his body was placed in a large water barrel known as a liger, and brandy was poured over it. This unusual operation was carried out in order to preserve Nelson's body until he returned to England, where he was to be buried, in accordance with his last wishes. While the Victory was undergoing repairs in Gibraltar, the brandy was generously diluted with wine spirit to better preserve the body. When the ship finally arrived home in December, Nelson's body was found to be perfectly preserved. On January 9, 1806, Nelson had a state funeral, after which he rested in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, the first non-royal person to be so honored.