An essay on the work on the topic: A brief review of V. Shalamov’s story Someone else’s Bread. Analysis of several stories from the series “Kolyma Stories” Analysis of the stories “At Night” and “Condensed Milk”: problems in “Kolyma Stories”

Depiction of man and camp life in V. Shalamov’s collection “Kolyma Stories”

The existence of a common man in the unbearably harsh conditions of camp life is the main theme of the collection “Kolyma Stories” by Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov. It conveys in a surprisingly calm tone all the sorrows and torments of human suffering. A very special writer in Russian literature, Shalamov was able to convey to our generation all the bitterness of human deprivation and moral loss. Shalamov's prose is autobiographical. He had to endure three terms in the camps for anti-Soviet agitation, 17 years in prison in total. He courageously withstood all the tests fate had prepared for him, was able to survive during this difficult time in these hellish conditions, but fate prepared for him a sad end - being of sound mind and full sanity, Shalamov ended up in an insane asylum, while he continued to write poetry, although I saw and heard poorly.

During Shalamov’s lifetime, only one of his stories, “Stlannik,” was published in Russia. It describes the characteristics of this northern evergreen tree. However, his works were actively published in the West. What's amazing is the height at which they are written. After all, these are real chronicles of hell, conveyed to us in the calm voice of the author. There is no prayer, no scream, no anguish. His stories contain simple, concise phrases, a short summary of the action, and only a few details. They have no background to the lives of the heroes, their past, no chronology, no description of the inner world, no author’s assessment. Shalamov’s stories are devoid of pathos; everything in them is very simple and sparing. The stories contain only the most important things. They are extremely condensed, usually taking only 2-3 pages, with a short title. The writer takes one event, or one scene, or one gesture. In the center of the work there is always a portrait, the executioner or the victim, in some stories both. The last phrase in the story is often compressed, laconic, like a sudden spotlight, it illuminates what happened, blinding us with horror. It is noteworthy that the arrangement of the stories in the cycle is of fundamental importance for Shalamov; they must follow exactly the way he placed them, that is, one after the other.

Shalamov's stories are unique not only in their structure, they have artistic novelty. His detached, rather cold tone gives the prose such an unusual effect. There is no horror in his stories, no overt naturalism, no so-called blood. The horror in them is created by the truth. Moreover, with a truth completely unthinkable given the time in which he lived. “Kolyma Tales” is a terrible evidence of the pain that people caused to other people just like them.

The writer Shalamov is unique in our literature. In his stories, he, as the author, suddenly becomes involved in the narrative. For example, in the story “Sherry Brandy” there is a narration from a dying poet, and suddenly the author himself includes his deep thoughts in it. The story is based on a semi-legend about the death of Osip Mandelstam, which was popular among prisoners in the Far East in the 30s. Sherry-Brandy is both Mandelstam and himself. Shalamov said directly that this is a story about himself, that there is less violation of historical truth here than in Pushkin’s Boris Godunov. He was also dying of hunger, he was on that Vladivostok transit, and in this story he includes his literary manifesto, and talks about Mayakovsky, Tyutchev, Blok, he turns to human erudition, even the name itself refers to this. “Sherry-Brandy” is a phrase from O. Mandelstam’s poem “I’ll tell you from the last one...”. In context it sounds like this:

"...I'll tell you from the last

Directness:

It's all just nonsense, sherry brandy,

My angel…"

The word “bredney” here is an anagram for the word “brandy”, and in general Sherry Brandy is a cherry liqueur. In the story itself, the author conveys to us the feelings of the dying poet, his last thoughts. First, he describes the pitiful appearance of the hero, his helplessness, hopelessness. The poet here dies for so long that he even ceases to understand it. His strength leaves him, and now his thoughts about bread are weakening. Consciousness, like a pendulum, leaves him at times. He then ascends somewhere, then returns again to the harsh present. Thinking about his life, he notes that he was always in a hurry to get somewhere, but now he is glad that there is no need to rush, he can think more slowly. For Shalamov’s hero, the special importance of the actual feeling of life, its value, and the impossibility of replacing this value with any other world becomes obvious. His thoughts rush upward, and now he is talking “... about the great monotony of achievements before death, about what doctors understood and described earlier than artists and poets.” While dying physically, he remains alive spiritually, and gradually the material world disappears around him, leaving room only for the world of inner consciousness. The poet thinks about immortality, considering old age only an incurable disease, only an unsolved tragic misunderstanding that a person could live forever until he gets tired, but he himself is not tired. And lying in the transit barracks, where everyone feels the spirit of freedom, because there is a camp in front, a prison behind, he remembers the words of Tyutchev, who, in his opinion, deserved creative immortality.

"Blessed is he who has visited this world

His moments are fatal.”

The “fatal moments” of the world are correlated here with the death of the poet, where the inner spiritual universe is the basis of reality in “Sherry Brandy.” His death is also the death of the world. At the same time, the story says that “these reflections lacked passion,” that the poet had long been overcome by indifference. He suddenly realized that all his life he had lived not for poetry, but for poetry. His life is an inspiration, and he was glad to realize this now, before his death. That is, the poet, feeling that he is in such a borderline state between life and death, is a witness to these very “fateful minutes.” And here, in his expanded consciousness, the “last truth” was revealed to him, that life is inspiration. The poet suddenly saw that he was two people, one composing phrases, the other discarding the unnecessary. There are also echoes of Shalamov’s own concept here, in which life and poetry are one and the same thing, that you need to discard the world creeping onto paper, leaving what can fit on this paper. Let's return to the text of the story, realizing this, the poet realized that even now he is composing real poems, even if they are not written down, not published - this is just vanity of vanities. “The best thing is that which is not written down, that which was composed and disappeared, melted away without a trace, and only the creative joy that he feels and which cannot be confused with anything, proves that the poem was created, that the beautiful was created.” The poet notes that the best poems are those born unselfishly. Here the hero asks himself whether his creative joy is unmistakable, whether he has made any mistakes. Thinking about this, he remembers Blok’s last poems, their poetic helplessness.

The poet was dying. Periodically, life entered and left him. For a long time he could not see the image in front of him until he realized that it was his own fingers. He suddenly remembered his childhood, a random Chinese passer-by who declared him the owner of a true sign, a lucky man. But now he doesn’t care, the main thing is that he hasn’t died yet. Talking about death, the dying poet remembers Yesenin and Mayakovsky. His strength was leaving him, even the feeling of hunger could not make his body move. He gave the soup to a neighbor, and for the last day his food was only a mug of boiling water, and yesterday’s bread was stolen. He lay there mindlessly until the morning. In the morning, having received his daily bread ration, he dug into it with all his might, feeling neither the scurvy pain nor the bleeding gums. One of his neighbors warned him to save some of the bread for later. "- When later? - he said distinctly and clearly.” Here, with particular depth, with obvious naturalism, the writer describes to us the poet with bread. The image of bread and red wine (Sherry Brandy resembles red wine in appearance) is not accidental in the story. They refer us to biblical stories. When Jesus broke the blessed bread (his body), shared it with others, took the cup of wine (his blood shed for many), and everyone drank from it. All this resonates very symbolically in this story by Shalamov. It is no coincidence that Jesus uttered his words just after he learned about the betrayal; they conceal a certain predestination of imminent death. The boundaries between worlds are erased, and bloody bread here is like a bloody word. It is also noteworthy that the death of a real hero is always public, it always gathers people around, and here a sudden question to the poet from neighbors in misfortune also implies that the poet is a real hero. He is like Christ, dying to gain immortality. Already in the evening, the soul left the pale body of the poet, but the resourceful neighbors kept him for two more days in order to receive bread for him. At the end of the story it is said that the poet thus died earlier than his official date of death, warning that this is an important detail for future biographers. In fact, the author himself is the biographer of his hero. The story “Sherry-Brandy” vividly embodies Shalamov’s theory, which boils down to the fact that a real artist emerges from hell to the surface of life. This is the theme of creative immortality, and the artistic vision here comes down to a double existence: beyond life and within it.

The camp theme in Shalamov's works is very different from the camp theme of Dostoevsky. For Dostoevsky, hard labor was a positive experience. Hard labor restored him, but his hard labor compared to Shalamov’s is a sanatorium. Even when Dostoevsky published the first chapters of Notes from the House of the Dead, censorship forbade him to do so, since a person feels very free there, too easily. And Shalamov writes that the camp is a completely negative experience for a person; not a single person became better after the camp. Shalamov has an absolutely unconventional humanism. Shalamov talks about things that no one has said before him. For example, the concept of friendship. In the story “Dry Rations,” he says that friendship is impossible in the camp: “Friendship is not born either in need or in trouble. Those “difficult” conditions of life that, as fairy tales of fiction tell us, are a prerequisite for the emergence of friendship, are simply not difficult enough. If misfortune and need brought people together and gave birth to friendship, it means that this need is not extreme and the misfortune is not great. Grief is not acute and deep enough if you can share it with friends. In real need, only one’s own mental and physical strength is learned, the limits of one’s capabilities, physical endurance and moral strength are determined.” And he returns to this topic again in another story, “Single Measurement”: “Dugaev was surprised - he and Baranov were not friends. However, with hunger, cold and insomnia, no friendship can be formed, and Dugaev, despite his youth, understood the falsity of the saying about friendship being tested by misfortune and misfortune.” In fact, all those concepts of morality that are possible in everyday life are distorted in the conditions of camp life.

In the story “The Snake Charmer,” the intellectual film scriptwriter Platonov “squeezes novels” to the thieves Fedenka, while reassuring himself that this is better, more noble, than enduring a bucket. Still, here he will awaken interest in the artistic word. He realizes that he still has a good place (at the stew, he can smoke, etc.). At the same time, at dawn, when Platonov, already completely weakened, finished telling the first part of the novel, the criminal Fedenka told him: “Lie here with us. You won't have to sleep much - it's dawn. You'll sleep at work. Gain strength for the evening...” This story shows all the ugliness of relations between prisoners. The thieves here ruled over the rest, they could force anyone to scratch their heels, “squeeze novels”, give up a place on the bunk or take away any thing, otherwise - a noose on the neck. The story “To the Presentation” describes how such thieves stabbed to death one prisoner in order to take away his knitted sweater - the last transfer from his wife before being sent on a long journey, which he did not want to give away. This is the real limit of the fall. At the beginning of the same story, the author conveys “big greetings” to Pushkin - the story begins in Shalamov’s “they were playing cards with the horseman Naumov,” and in Pushkin’s story “The Queen of Spades” the beginning was like this: “Once we were playing cards with the horse guard Narumov.” Shalamov has his own secret game. He keeps in mind the entire experience of Russian literature: Pushkin, Gogol, and Saltykov-Shchedrin. However, he uses it in very measured doses. Here, an unobtrusive and accurate hit right on target. Despite the fact that Shalamov was called the chronicler of those terrible tragedies, he still believed that he was not a chronicler and, moreover, was against teaching life in works. The story “The Last Battle of Major Pugachev” shows the motive of freedom and gaining freedom at the expense of one’s life. This is a tradition characteristic of the Russian radical intelligentsia. The connection of times is broken, but Shalamov ties the ends of this thread. But speaking of Chernyshevsky, Nekrasov, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, he blamed such literature for inciting social illusions.

Initially, it may seem to a new reader that Shalamov’s “Kolyma Tales” are similar to Solzhenitsyn’s prose, but this is far from the case. Initially, Shalamov and Solzhenitsyn are incompatible - neither aesthetically, nor ideologically, nor psychologically, nor literary and artistically. These are two completely different, incomparable people. Solzhenitsyn wrote: “True, Shalamov’s stories did not satisfy me artistically: in all of them I lacked characters, faces, the past of these persons and some kind of separate outlook on life for each.” And one of the leading researchers of Shalamov’s work, V. Esipov: “Solzhenitsyn clearly sought to humiliate and trample Shalamov.” On the other hand, Shalamov, having highly praised One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, wrote in one of his letters that he strongly disagreed with Ivan Denisovich in terms of the interpretation of the camp, that Solzhenitsyn did not know and did not understand the camp. He is surprised that Solzhenitsyn has a cat near the kitchen. What kind of camp is this? In real camp life, this cat would have been eaten long ago. Or he was also interested in why Shukhov needed a spoon, since the food was so liquid that it could be drunk simply over the side. Somewhere he also said, well, another varnisher appeared, he was sitting on a sharashka. They have the same topic, but different approaches. Writer Oleg Volkov wrote: “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” by Solzhenitsyn not only did not exhaust the theme of “Russia behind barbed wire”, but represents, albeit talented and original, but still a very one-sided and incomplete attempt to illuminate and comprehend one of the most terrible periods in the history of our country " And one more thing: “The illiterate Ivan Shukhov is in a sense a person belonging to the past - now you don’t often meet an adult Soviet person who would perceive reality so primitively, uncritically, whose worldview would be so limited as that of Solzhenitsyn’s hero.” O. Volkov opposes the idealization of labor in the camp, and Shalamov says that camp labor is a curse and corruption of man. Volkov highly appreciated the artistic side of the stories and wrote: “Shalamov’s characters are trying, unlike Solzhenitsynsky, to comprehend the misfortune that has befallen them, and in this analysis and comprehension lies the enormous significance of the stories under review: without such a process it will never be possible to uproot the consequences of the evil that we have inherited from Stalin's rule." Shalamov refused to become a co-author of “The Gulag Archipelago” when Solzhenitsyn offered him co-authorship. At the same time, the very concept of “The Gulag Archipelago” included the publication of this work not in Russia, but outside its borders. Therefore, in the dialogue that took place between Shalamov and Solzhenitsyn, Shalamov asked, I want to know for whom I am writing. In their work, Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov, when creating artistic and documentary prose, rely on different life experiences and different creative attitudes. This is one of their most important differences.

Shalamov's prose is structured in such a way as to allow a person to experience what he cannot experience for himself. It tells in simple and understandable language about the camp life of ordinary people during that particularly oppressive period of our history. This is what makes Shalamov’s book not a list of horrors, but genuine literature. In essence, this is philosophical prose about a person, about his behavior in unthinkable, inhuman conditions. Shalamov’s “Kolyma Stories” is at the same time a story, a physiological essay, and a study, but first of all it is a memory, which is valuable for this reason, and which must certainly be conveyed to the future generation.

Bibliography:

1. A. I. Solzhenitsyn and Russian culture. Vol. 3. – Saratov, Publishing Center “Science”, 2009.

2. Varlam Shalamov 1907 - 1982: [electronic resource]. URL: http://shalamov.ru.

3. Volkov, O. Varlam Shalamov “Kolyma Tales” // Banner. - 2015. - No. 2.

4. Esipov, V. Provincial disputes at the end of the twentieth century / V. Esipov. – Vologda: Griffin, 1999. - P. 208.

5. Kolyma stories. – M.: Det. Lit., 2009.

6. Minnullin O.R. Intertextual analysis of Varlam Shalamov's story "Sherry Brandy": Shalamov - Mandelstam - Tyutchev - Verlaine // Philological studios. - Krivoy Rog National University. – 2012. – Issue 8. - pp. 223 - 242.

7. Solzhenitsyn, A. With Varlam Shalamov // New World. - 1999. - No. 4. - P. 164.

8. Shalamov, V. Kolyma stories / V. Shalamov. – Moscow: Det. Lit., 2009.

9. Shalamov collection. Vol. 1. Comp. V.V. Esipov. - Vologda, 1994.

10. Shalamov collection: Vol. 3. Comp. V.V. Esipov. - Vologda: Griffin, 2002.

11. Shklovsky E. The truth of Varlam Shalamov // Shalamov V. Kolyma stories. – M.: Det. Lit., 2009.

Brief review of V. Shalamov’s story “Alien Bread”

The story was written in 1967, after V.T. Shalamov left the camp. The author spent a total of eighteen years in prison, and all of his work is devoted to the theme of camp life.

A distinctive feature of his heroes is that they no longer hope for anything and do not believe in anything. They lost all human feelings, except hunger and cold. It is in the story of ChKh that this characteristic of the camp inmate manifests itself especially clearly. A friend entrusted the main character with a bag of bread.

It was extremely difficult for him to restrain himself from touching the rations: +I did not sleep+ because I had bread in my head+ You can imagine how difficult it was for the camp inmate then.

But the main thing that helped me survive was self-respect. You cannot compromise your pride, conscience and honor under any circumstances. And the main character showed not only all these qualities, but also strength of character, will, and endurance. He did not eat his comrade’s bread, and thus, as if he did not betray him, he remained faithful to him. I believe that this act is important primarily for the hero himself. He remained faithful not so much to his comrade as to himself: And I fell asleep, proud that I had not stolen my comrade’s bread.

This story made a great impression on me. It fully reflects the terrible, unbearable conditions in which the camp inmate lived. And yet the author shows that the Russian people, no matter what, do not deviate from their beliefs and principles. And this helps him survive to some extent.

Bibliography

To prepare this work, materials were used from the site http://www.coolsoch.ru/

Composition

A short review of V. Shalamov’s story Someone else’s Bread.

ChKh's story was written in 1967, after V.T. Shalamov left the camp. In conclusion, the author

spent a total of eighteen years, and all of his work is devoted to the theme of camp life.

A distinctive feature of his heroes is that they no longer hope for anything and do not believe in anything.

believe. They lost all human feelings, except hunger and cold. It is in the story that CHH is like this

the characteristic of the camp inmate is especially pronounced. The main character was entrusted by a comrade with a small bag with

breadmm. It was extremely difficult for him to restrain himself from touching the soldering: +I did not sleep+ because in

I had bread in my head+ You can imagine how hard it was for the camper then. But the main thing is that

Self-respect helped me survive. You cannot compromise your pride, conscience and honor in any way.

circumstances. And the main character showed not only all these qualities, but also strength of character,

will, endurance. He did not eat his comrade’s bread, and thus, as if he had not betrayed him, he remained with him

true. I believe that this act is important primarily for the hero himself. He remained faithful

as much to his comrade as to himself: And I fell asleep, proud that I had not stolen my comrade’s bread.

This story made a great impression on me. It fully reflects those terrible

the unbearable conditions in which the camp inmate lived. And yet the author shows that Russian

a person, no matter what, does not deviate from his beliefs and principles. And this helps in some way

degree to which he can survive.

Analysis of several stories from the series “Kolyma Tales”

General analysis of “Kolyma Tales”

It is difficult to imagine how much emotional stress these stories cost Shalamov. I would like to dwell on the compositional features of “Kolyma Tales”. The plots of the stories at first glance are unrelated to each other, however, they are compositionally integral. “Kolyma Stories” consists of 6 books, the first of which is called “Kolyma Stories”, followed by the books “Left Bank”, “Shovel Artist”, “Sketches of the Underworld”, “Resurrection of the Larch”, “The Glove, or KR-2".

In V. Shalamov’s manuscript “Kolyma Stories” there are 33 stories - both very small (1 to 3 pages), and larger ones. You can immediately feel that they were written by a qualified, experienced writer. Most are read with interest, have a sharp plot (but even the plotless short stories are constructed thoughtfully and interestingly), written in a clear and figurative language (and even, although they tell mainly about the “thieves’ world,” there is no sense of argotism in the manuscript). So, if we are talking about editing in the sense of stylistic corrections, “tweaking” the composition of stories, etc., then the manuscript, in essence, does not need such revision.

Shalamov is a master of naturalistic descriptions. Reading his stories, we are immersed in the world of prisons, transit points, and camps. The stories are narrated in third person. The collection is like an eerie mosaic, each story is a photographic piece of the everyday life of prisoners, very often “thieves”, thieves, swindlers and murderers in prison. All of Shalamov’s heroes are different people: military and civilian, engineers and workers. They got used to camp life and absorbed its laws. Sometimes, looking at them, we don’t know who they are: whether they are intelligent creatures or animals in which only one instinct lives - to survive at all costs. The scene from the story “Duck” seems comical to us, when a man tries to catch a bird, and it turns out to be smarter than him. But we gradually understand the tragedy of this situation, when the “hunt” led to nothing but forever frostbitten fingers and lost hopes about the possibility of being crossed off from the “ominous list.” But people still have ideas about mercy, compassion, and conscientiousness. It’s just that all these feelings are hidden under the armor of the camp experience, which allows you to survive. Therefore, it is considered disgraceful to deceive someone or eat food in front of hungry companions, as the hero of the story “Condensed Milk” does. But the strongest thing in prisoners is the thirst for freedom. Let it be for a moment, but they wanted to enjoy it, feel it, and then die is not scary, but in no case be captured - there is death. Therefore, the main character of the story “The Last Battle of Major Pugachev” prefers to kill himself rather than surrender.

“We have learned humility, we have forgotten how to be surprised. We had no pride, selfishness, selfishness, and jealousy and passion seemed to us Martian concepts, and, moreover, trifles,” wrote Shalamov.

The author describes in great detail (by the way, there are a number of cases when the same - literally, word for word - descriptions of certain scenes appear in several stories) - how they sleep, wake up, eat, walk, dress, work, “ prisoners having fun; how brutally the guards, doctors, and camp authorities treat them. Each story talks about constantly sucking hunger, about constant cold, illness, about backbreaking hard labor that makes you fall off your feet, about continuous insults and humiliations, about the fear that never leaves the soul for a minute of being offended, beaten, maimed, stabbed to death by “thieves.” ”, of whom the camp authorities are also afraid. Several times V. Shalamov compares the life of these camps with Dostoevsky’s “Notes from the House of the Dead” and each time comes to the conclusion that Dostoevsky’s “House of the Dead” is an earthly paradise compared to what the characters in “Kolyma Tales” experience. The only people who prosper in the camps are thieves. They rob and kill with impunity, terrorize doctors, pretend, do not work, give bribes left and right - and live well. There is no control over them. Constant torment, suffering, exhausting work that drives you to the grave - this is the lot of honest people who are driven here on charges of counter-revolutionary activities, but in fact are people innocent of anything.

And here we see “frames” of this terrible narrative: murders during a card game (“At the Presentation”), digging up corpses from graves for robbery (“At Night”), insanity (“Rain”), religious fanaticism (“Apostle Paul” ), death (“Aunt Polya”), murder (“First Death”), suicide (“Seraphim”), the unlimited dominion of thieves (“Snake Charmer”), barbaric methods of identifying simulation (“Shock Therapy”), murders of doctors (“Snake Charmer”). Red Cross"), killing prisoners by convoy ("Berry"), killing dogs ("Bitch Tamara"), eating human corpses ("Golden Taiga") and so on and everything in the same spirit.

Moreover, all descriptions are very visible, very detailed, often with numerous naturalistic details.

Basic emotional motives run through all the descriptions - a feeling of hunger that turns every person into a beast, fear and humiliation, slow dying, boundless tyranny and lawlessness. All this is photographed, strung together, horrors are piled up without any attempt to somehow comprehend everything, to understand the causes and consequences of what is being described.

If we talk about the skill of Shalamov the artist, about his manner of presentation, then it should be noted that the language of his prose is simple, extremely precise. The intonation of the narration is calm, without strain. Severely, laconically, without any attempts at psychological analysis, the writer even talks about what is happening somewhere documented. Shalamov achieves a stunning effect on the reader by contrasting the calmness of the author’s unhurried, calm narrative and the explosive, terrifying content

What is surprising is that the writer never falls into a pathetic breakdown, nowhere does he crumble into curses against fate or power. He leaves this privilege to the reader, who, willy-nilly, will shudder while reading each new story. After all, he will know that all this is not the author’s imagination, but the cruel truth, albeit clothed in artistic form.

The main image that unites all the stories is the image of the camp as absolute evil. Shalamova views the GULAG as an exact copy of the model of totalitarian Stalinist society: “...The camp is not a contrast between hell and heaven. and the cast of our life... The camp... is world-like.” Camp - hell - is a constant association that comes to mind while reading “Kolyma Tales”. This association arises not even because you are constantly faced with the inhuman torment of prisoners, but also because the camp seems to be the kingdom of the dead. Thus, the story “Funeral Word” begins with the words: “Everyone died...” On every page you encounter death, which here can be named among the main characters. All heroes, if we consider them in connection with the prospect of death in the camp, can be divided into three groups: the first - heroes who have already died, and the writer remembers them; the second - those who will almost certainly die; and the third group are those who may be lucky, but this is not certain. This statement becomes most obvious if we remember that the writer in most cases talks about those whom he met and whom he experienced in the camp: a man who was shot for failure to carry out the plan by his site, his classmate, whom he met 10 years later in the Butyrskaya cell prison, a French communist whom the foreman killed with one blow of his fist...

Varlam Shalamov lived through his entire life again, writing a rather difficult work. Where did he get his strength from? Perhaps everything was so that one of those who remained alive would convey in words the horrors of the Russian people on their own land. My idea of life as a blessing, as happiness, has changed. Kolyma taught me something completely different. The principle of my age, my personal existence, my entire life, a conclusion from my personal experience, a rule learned by this experience, can be expressed in a few words. First you need to return the slaps and only secondly the alms. Remember evil before good. To remember all the good things is for a hundred years, and all the bad things are for two hundred years. This is what distinguishes me from all Russian humanists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.” (V. Shalamov)

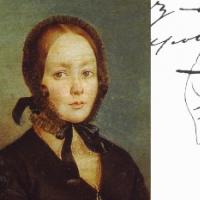

Let's look at Shalamov's collection, on which he worked from 1954 to 1962. Let us describe its brief content. "Kolyma Stories" is a collection whose plot is a description of the camp and prison life of Gulag prisoners, their tragic destinies, similar to one another, in which chance rules. The author’s focus is constantly on hunger and satiety, painful dying and recovery, exhaustion, moral humiliation and degradation. You will learn more about the problems raised by Shalamov by reading the summary. “Kolyma Stories” is a collection that is an understanding of what the author experienced and saw during the 17 years he spent in prison (1929-1931) and Kolyma (from 1937 to 1951). The author's photo is presented below.

Funeral word

The author recalls his comrades from the camps. We will not list their names, since we are making a brief summary. "Kolyma Stories" is a collection in which fiction and documentary are intertwined. However, all killers are given a real last name in the stories.

Continuing the narrative, the author describes how the prisoners died, what torture they endured, talks about their hopes and behavior in “Auschwitz without ovens,” as Shalamov called the Kolyma camps. Few managed to survive, and only a few managed to survive and not break morally.

"The Life of Engineer Kipreev"

Let us dwell on the following interesting story, which we could not help but describe when compiling a summary. “Kolyma Stories” is a collection in which the author, who has not sold or betrayed anyone, says that he has developed for himself a formula for protecting his own existence. It consists in the fact that a person can survive if he is ready to die at any moment, he can commit suicide. But later he realizes that he only built a comfortable shelter for himself, since it is unknown what you will become at the decisive moment, whether you will have enough not only mental strength, but also physical strength.

Kipreev, a physics engineer arrested in 1938, was not only able to withstand interrogation and beating, but even attacked the investigator, as a result of which he was put in a punishment cell. But still they are trying to get him to give false testimony, threatening to arrest his wife. Kipreev nevertheless continues to prove to everyone that he is not a slave, like all prisoners, but a human being. Thanks to his talent (he fixed a broken one and found a way to restore burnt out light bulbs), this hero manages to avoid the most difficult work, but not always. It is only by a miracle that he survives, but the moral shock does not let him go.

"To the show"

Shalamov, who wrote “Kolyma Stories,” a brief summary of which interests us, testifies that camp corruption affected everyone to one degree or another. It was carried out in various forms. Let us describe in a few words another work from the collection “Kolyma Tales” - “To the Show”. A summary of its plot is as follows.

Two thieves are playing cards. One loses and asks to play in debt. Enraged at some point, he orders an unexpectedly imprisoned intellectual, who happened to be among the spectators, to give up his sweater. He refuses. One of the thieves “finishes” him, but the sweater goes to the thieves anyway.

"At night"

Let's move on to the description of another work from the collection "Kolyma Stories" - "At Night". Its summary, in our opinion, will also be interesting to the reader.

Two prisoners sneak towards the grave. The body of their comrade was buried here in the morning. They take off the dead man's linen in order to exchange it for tobacco or bread tomorrow or sell it. Disgust for the clothes of the deceased is replaced by the thought that perhaps tomorrow they will be able to smoke or eat a little more.

There are a lot of works in the collection "Kolyma Stories". "The Carpenters", a summary of which we have omitted, follows the story "Night". We invite you to familiarize yourself with it. The product is small in volume. The format of one article, unfortunately, does not allow us to describe all the stories. Also a very small work from the collection "Kolyma Tales" - "Berry". A summary of the main and, in our opinion, most interesting stories is presented in this article.

"Single metering"

Defined by the author as slave labor in camps, it is another form of corruption. The prisoner, exhausted by it, cannot work his quota; labor turns into torture and leads to slow death. Dugaev, a prisoner, is becoming increasingly weaker due to the 16-hour working day. He pours, picks, carries. In the evening, the caretaker measures what he has done. The figure of 25% mentioned by the caretaker seems very large to Dugaev. His hands, head, and calves ache unbearably. The prisoner no longer even feels hungry. Later he is called to the investigator. He asks: “First name, last name, term, article.” Every other day, soldiers take the prisoner to a remote place surrounded by a fence with barbed wire. At night you can hear the noise of tractors from here. Dugaev realizes why he was brought here and understands that his life is over. He only regrets that he suffered an extra day in vain.

"Rain"

You can talk for a very long time about such a collection as “Kolyma Stories”. The summary of the chapters of the works is for informational purposes only. We bring to your attention the following story - "Rain".

"Sherry Brandy"

The prisoner poet, who was considered the first poet of the 20th century in our country, dies. He lies on the bunks, in the depths of their bottom row. It takes a long time for a poet to die. Sometimes a thought comes to him, for example, that someone stole bread from him, which the poet put under his head. He is ready to search, fight, swear... However, he no longer has the strength to do this. When the daily ration is placed in his hand, he presses the bread to his mouth with all his might, sucks it, tries to gnaw and tear with his loose, scurvy-infested teeth. When a poet dies, he is not written off for another 2 days. During the distribution, the neighbors manage to get bread for him as if he were alive. They arrange for him to raise his hand like a puppet.

"Shock therapy"

Merzlyakov, one of the heroes of the collection “Kolma Stories”, a brief summary of which we are considering, is a convict of large build, and in general work he understands that he is failing. He falls, cannot get up and refuses to take the log. First his own people beat him, then his guards. He is brought to camp with lower back pain and a broken rib. After recovery, Merzlyakov does not stop complaining and pretends that he cannot straighten up. He does this in order to delay discharge. He is sent to the surgical department of the central hospital, and then to the nervous department for examination. Merzlyakov has a chance to be released due to illness. He tries his best not to be exposed. But Pyotr Ivanovich, a doctor, himself a former prisoner, exposes him. Everything human in him replaces the professional. He spends most of his time exposing those who are simulating. Pyotr Ivanovich anticipates the effect that the case with Merzlyakov will produce. The doctor first gives him anesthesia, during which he manages to straighten Merzlyakov’s body. A week later, the patient is prescribed shock therapy, after which he asks to be discharged himself.

"Typhoid quarantine"

Andreev ends up in quarantine after falling ill with typhus. The patient's position, compared to working in the mines, gives him a chance to survive, which he almost did not hope for. Then Andreev decides to stay here as long as possible, and then, perhaps, he will no longer be sent to the gold mines, where there is death, beatings, and hunger. Andreev does not respond to the roll call before sending those who have recovered to work. He manages to hide in this way for quite a long time. The transit bus gradually empties, and finally it’s Andreev’s turn. But it seems to him now that he has won the battle for life, and if there are any deployments now, it will only be on local, short-term business trips. But when a truck with a group of prisoners who were unexpectedly given winter uniforms crosses the line separating long- and short-term business trips, Andreev realizes that fate has laughed at him.

The photo below shows the house in Vologda where Shalamov lived.

"Aortic aneurysm"

In Shalamov's stories, illness and hospital are an indispensable attribute of the plot. Ekaterina Glovatskaya, a prisoner, ends up in the hospital. Zaitsev, the doctor on duty, immediately liked this beauty. He knows that she is in a relationship with prisoner Podshivalov, an acquaintance of his who runs a local amateur art group, but the doctor still decides to try his luck. As usual, he begins with a medical examination of the patient, listening to the heart. However, male interest is replaced by medical concern. In Glowacka he discovers this is a disease in which every careless movement can provoke death. The authorities, who have made it a rule to separate lovers, have once already sent the girl to a penal women's mine. The head of the hospital, after the doctor’s report about her illness, is sure that this is the machinations of Podshivalov, who wants to detain his mistress. The girl is discharged, but during loading she dies, which is what Zaitsev warned about.

"The Last Battle of Major Pugachev"

The author testifies that after the Great Patriotic War, prisoners who fought and went through captivity began to arrive in the camps. These people are of a different kind: they know how to take risks, they are brave. They only believe in weapons. Camp slavery did not corrupt them; they were not yet exhausted to the point of losing their will and strength. Their “fault” was that these prisoners were captured or surrounded. It was clear to one of them, Major Pugachev, that they had been brought here to die. Then he gathers strong and determined prisoners to match himself, who are ready to die or become free. The escape is prepared all winter. Pugachev realized that only those who managed to avoid general work could escape after surviving the winter. One by one, the participants in the conspiracy are promoted to service. One of them becomes a cook, another becomes a cult leader, the third repairs weapons for security.

One spring day, at 5 am, there was a knock on the watch. The duty officer lets in the prisoner cook, who, as usual, has come to get the keys to the pantry. The cook strangles him, and another prisoner dresses in his uniform. The same thing happens to other duty officers who returned a little later. Then everything happens according to Pugachev’s plan. The conspirators burst into the security room and seize weapons, shooting the guard on duty. They stock up on provisions and put on military uniforms, holding the suddenly awakened soldiers at gunpoint. Having left the camp territory, they stop the truck on the highway, disembark the driver and drive until the gas runs out. Then they go into the taiga. Pugachev, waking up at night after many months of captivity, recalls how in 1944 he escaped from a German camp, crossed the front line, survived interrogation in a special department, after which he was accused of espionage and sentenced to 25 years in prison. He also recalls how emissaries of General Vlasov came to the German camp and recruited Russians, convincing them that the captured soldiers were traitors to the Motherland for the Soviet regime. Pugachev did not believe them then, but soon became convinced of this himself. He looks lovingly at his comrades sleeping nearby. A little later, a hopeless battle ensues with the soldiers who surrounded the fugitives. Almost all of the prisoners die, except one, who is nursed back to health after being seriously wounded in order to be shot. Only Pugachev manages to escape. He is hiding in a bear's den, but he knows that they will find him too. He doesn't regret what he did. His last shot is at himself.

So, we looked at the main stories from the collection, authored by Varlam Shalamov (“Kolyma Stories”). A summary introduces the reader to the main events. You can read more about them on the pages of the work. The collection was first published in 1966 by Varlam Shalamov. "Kolyma Stories", a brief summary of which you now know, appeared on the pages of the New York publication "New Journal".

In New York in 1966, only 4 stories were published. The following year, 1967, 26 stories by this author, mainly from the collection of interest to us, were published in translation into German in the city of Cologne. During his lifetime, Shalamov never published the collection “Kolyma Stories” in the USSR. A summary of all the chapters, unfortunately, is not included in the format of one article, since there are a lot of stories in the collection. Therefore, we recommend that you familiarize yourself with the rest.

"Condensed milk"

In addition to those described above, we will tell you about one more work from the collection “Kolyma Stories” - Its summary is as follows.

Shestakov, an acquaintance of the narrator, did not work at the mine face, because he was a geological engineer, and he was hired into the office. He met with the narrator and said that he wanted to take the workers and go to the Black Keys, to the sea. And although the latter understood that this was impracticable (the path to the sea is very long), he nevertheless agreed. The narrator reasoned that Shestakov probably wants to hand over all those who will participate in this. But the promised condensed milk (to overcome the journey, he had to refresh himself) bribed him. Going to Shestakov, he ate two jars of this delicacy. And then he suddenly announced that he had changed his mind. A week later, other workers fled. Two of them were killed, three were tried a month later. And Shestakov was transferred to another mine.

We recommend reading other works in the original. Shalamov wrote “Kolyma Tales” very talentedly. The summary ("Berries", "Rain" and "Children's Pictures" we also recommend reading in the original) conveys only the plot. The author's style and artistic merits can only be assessed by becoming familiar with the work itself.

Not included in the collection "Kolyma Stories" "Sentence". We did not describe the summary of this story for this reason. However, this work is one of the most mysterious in Shalamov’s work. Fans of his talent will be interested in getting to know him.